Unaccompanied minors

By José Colón

ZAMPA Award Finalist

This narrative and audiovisual journalistic project, with a clear desire to focus attention on the institutional racism that defines the backbone of the children’s itineraries, is the result of a kind of laboratory that has the political will and decision not to reproduce the visual and narrative imaginary that has accompanied the story of “unaccompanied minors”.

After crossing 130 miles by ferry from southern Spain to the tiny Spanish colonial enclaves of Melilla and Ceuta in North Africa on the shores of the Mediterranean, travelers are greeted by the sight of a 16th-century fortress, its stone walls overlooking a sheer cliff.

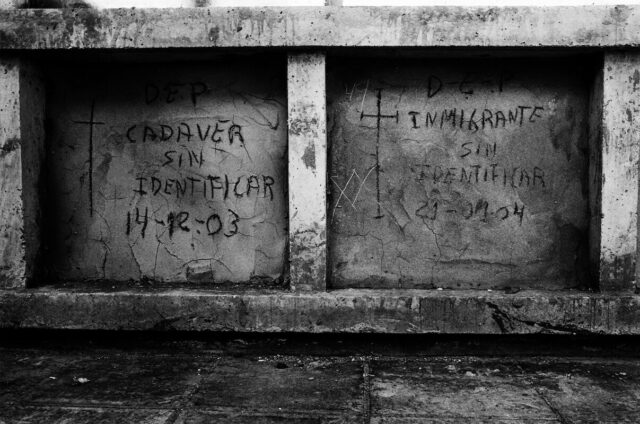

Hidden along the cliffs and in the woods, these children watch the ferry as it docks, and the line of trucks waiting to board it for the trip back to Spain, seeing them as their tickets to riches. A colonial enclave held by the Spanish since 1495, Melilla, a small port city once famous for its bustling trade in beeswax and goatskins, shares a seven-mile border with Morocco, defended by a 20-foot-high, triple-reinforced fence strung with barbed wire and topped with razor blades. Its objective is to keep out immigrants from sub-Saharan countries who lack passports to enter legally. Although the mesh is so thin that fingers cannot grasp it, thousands of foreigners manage to scale the barrier each year, using hooks to hoist themselves up and over it, although many are injured in the process.

Moroccan citizens from the border towns can enter legally, and hundreds of them do so every day through the only pedestrian checkpoint at the border. Most are workers and shoppers returning at the end of the day, but some hope to make their way from Melilla to the European mainland. Among those who enter alone, and do not leave, are children as young as 8 years old, many of whom make the trip with the blessing of their parents.

“They want to go to work and help their family, especially their mother and siblings in Morocco,” explains Spanish photojournalist José Colón, who has been photographing street children in Melilla and Ceuta, another Spanish enclave 250 miles away, opposite Gibraltar, for 15 years. Some, he says, “want to be soccer players,” to play on famous soccer teams.

Migrant children and young people are often not considered children and young people by the destination countries to which they migrate in Europe. If they were considered in such a way, the way they would be received and treated would be radically different. The way in which this story needs to be told is different.

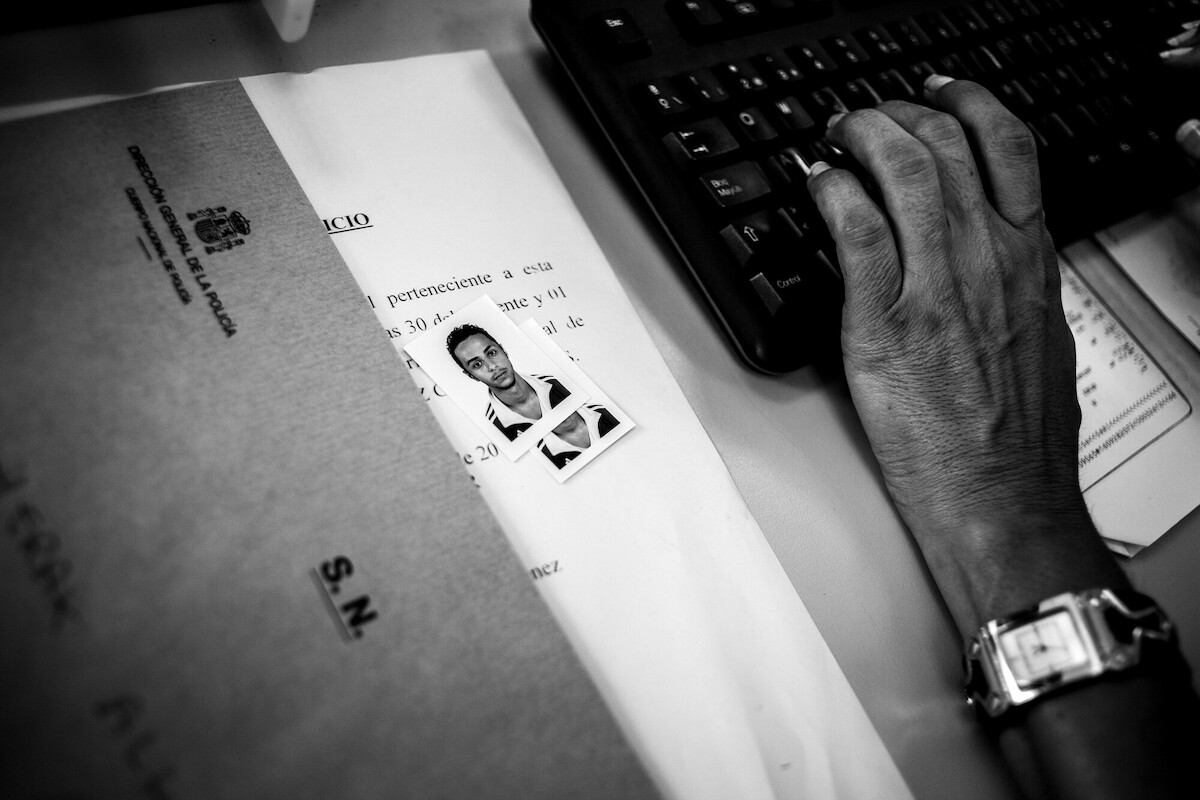

The processes of racialization to which migrant youth are subjected have stripped them of their own childhood and youth, placing them between the coordinates of criminalization and a highly unaccomplished institutional abandonment. And yet, the story of how the social construction of race is applied to them has been invisibilized. The (neo-)colonial relations between the countries of origin of these young people and the countries of destination, their economic, diplomatic or social relations are not part of the analysis.

It is a little more than 20 years since minors began to arrive and had to be received by an already deficient child protection system in Spain. Even so, the role of the administration and the State has been questioned exclusively from those spaces dedicated to alleviating the grievances that have resulted from a certain model of (dis)protection. Even for these critical sectors, which have done tireless work in denouncing and pointing out the prevarication of the guardianship entities, the relationship between race, class, migration and child protection has also been a blind question.

Recently, in this context, the presence of migrant minors in the Spanish State has gained notorious visibility in the media, in the mouths of the political class, and even -although to a lesser extent- among social action entities, usually recipients of public subsidies and activist movements.

The analyses and readings on the state of affairs in relation to child protection have had three outstanding trends. Blatant criminalization, exacerbated paternalism and institutional neglect. And always, without exception, a hyper-visibilization of children as the subject on which any plot pivots. This has led – especially in recent months – to an exposure that has made them the subject of tabloid news, the focus of security police operations, as well as the victim – not one, but several – of racist attacks in the streets and in the centers where they live, reaching the climax of several attempted attacks this fall.

This narrative and audiovisual journalistic project, with a clear desire to focus attention on the institutional racism that defines the backbone of the children’s itineraries, is the result of a kind of laboratory that has the political will and decision not to reproduce the visual and narrative imaginary that has accompanied the story of “unaccompanied minors”. The vitality of institutional racism has meant that when we want to talk about it, we do not talk about it, but about the “other” subjected to its power. Therefore, the image of the children will not be used to talk about institutional racism, nor will the strategies used by the youth to confront it be revealed.

About José Colón:

Seville, Spain 1975. Spanish freelance photojournalist specializing in migration, refugee and human rights issues based in Barcelona. His images have been shown in Spain, Italy, United States, Germany, France, Brazil, as well as in several international magazines. He has collaborated artistically with the Centro de Cultura Contemporánea de Barcelona, the Centro Cultural Internacional Oscar Niemeyer, the Museo de Historia de Barcelona and the Museo de Historia de Zaragoza. He works with several international newspapers and photo agencies.

Equipment:

Cameras: Nikon F2, Canon Mark II, Leica M Type 240, Sony R II

Lenses: 50 and 35mm

Links: