+13

+13 The great African portraitist

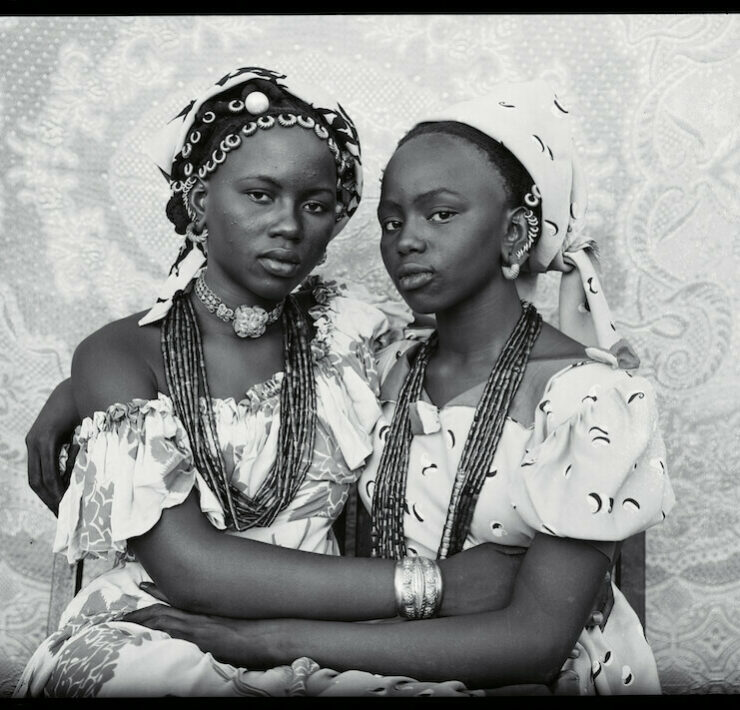

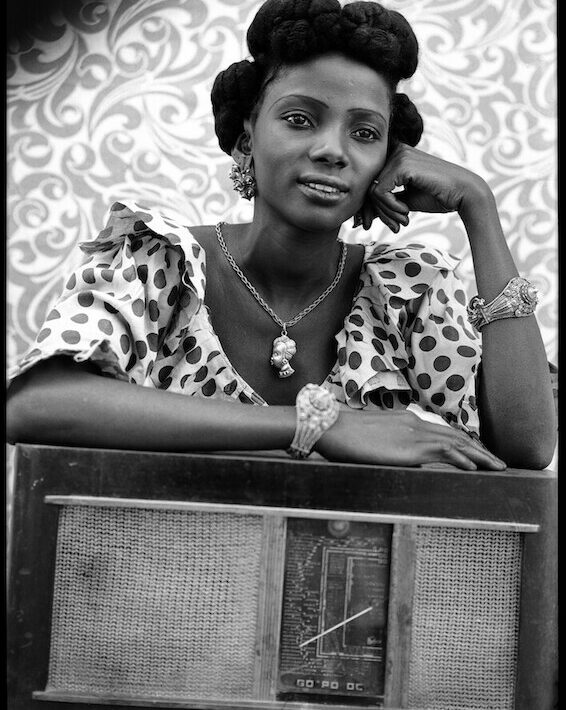

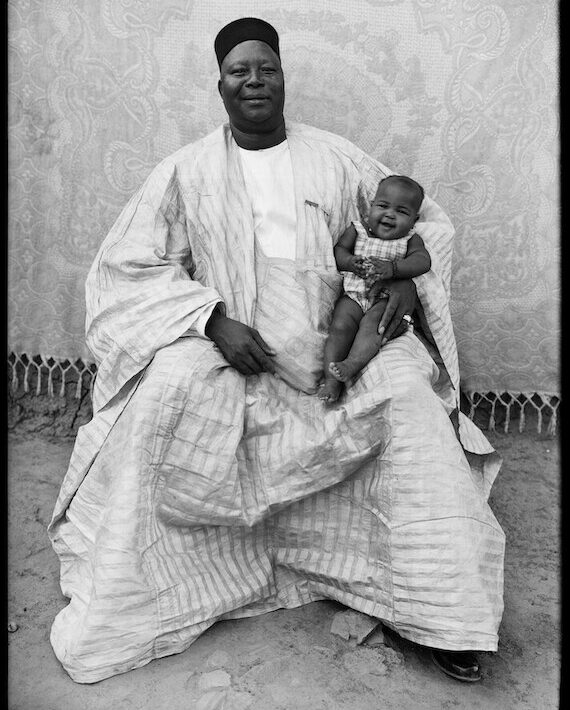

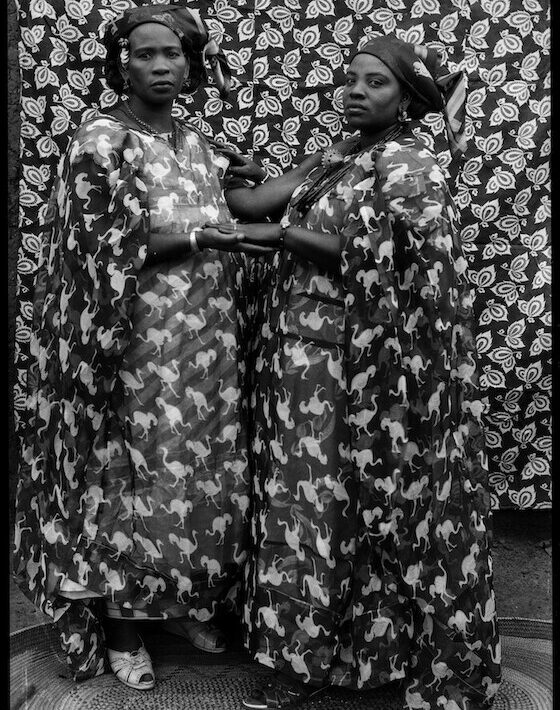

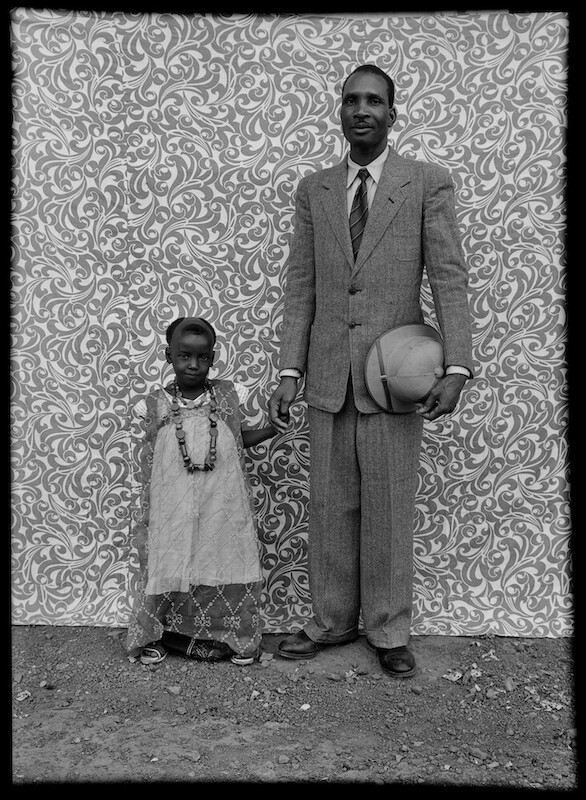

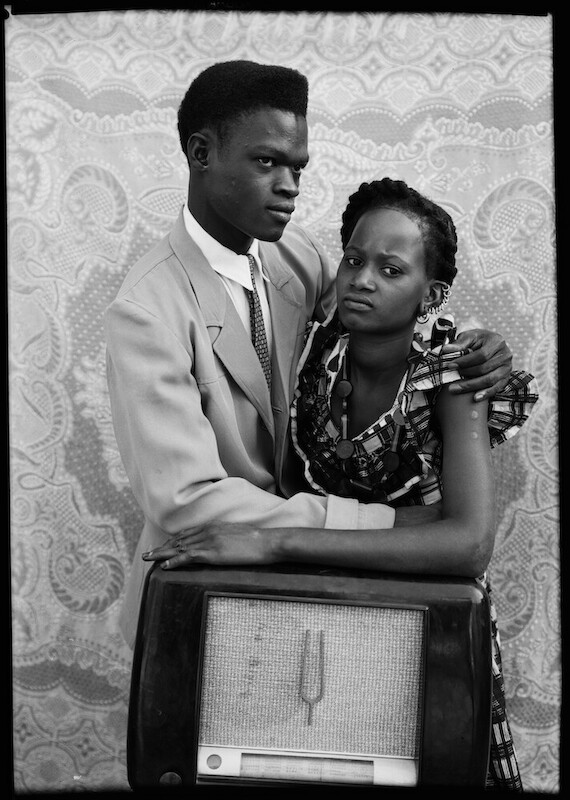

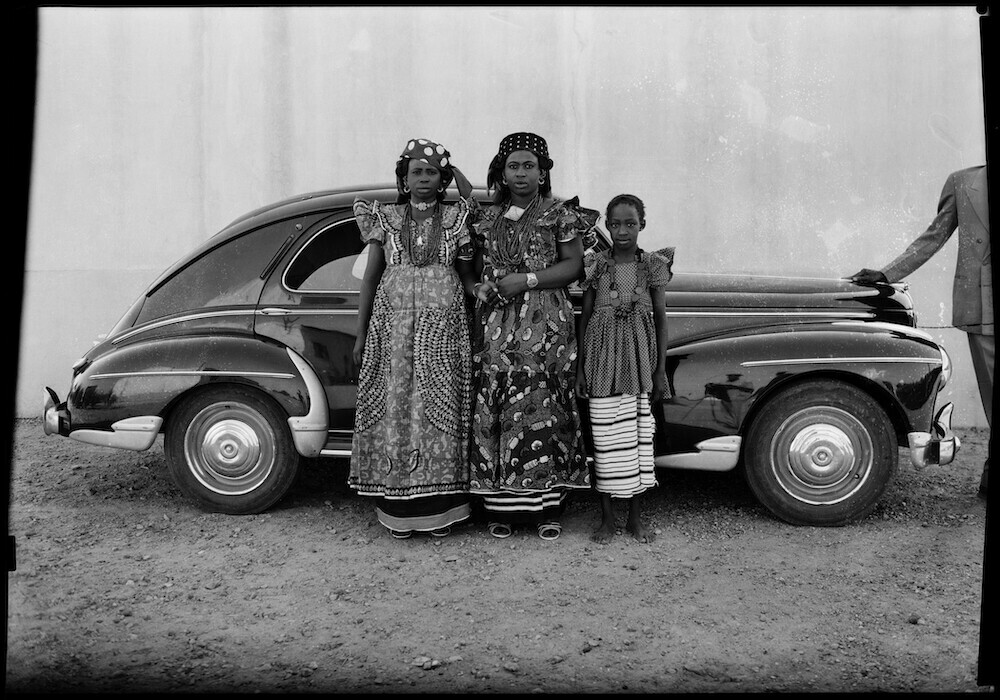

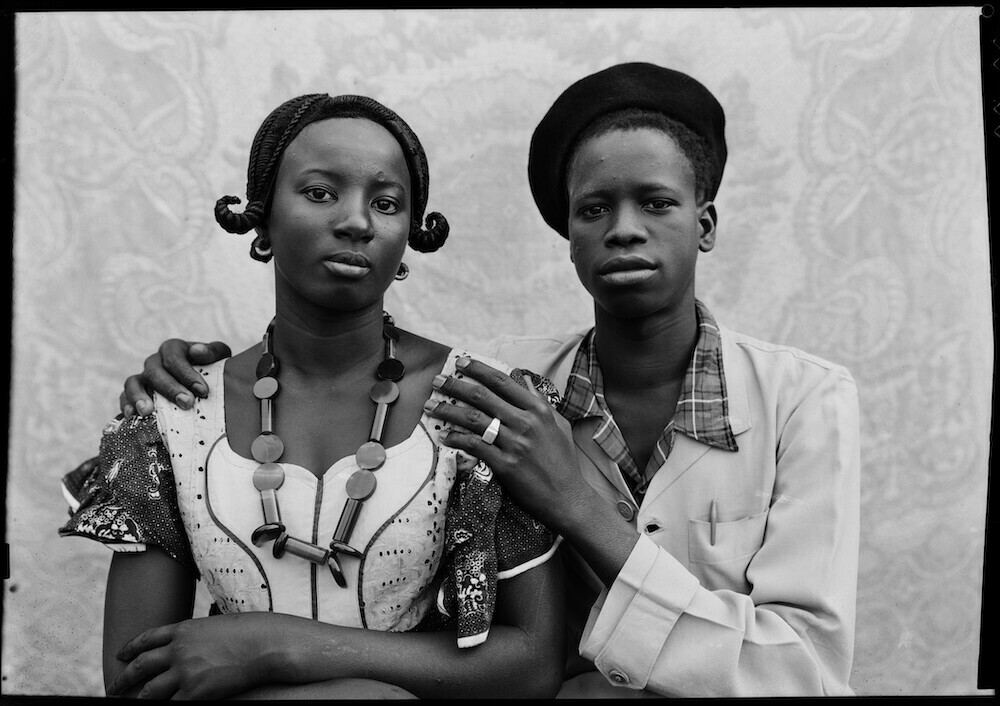

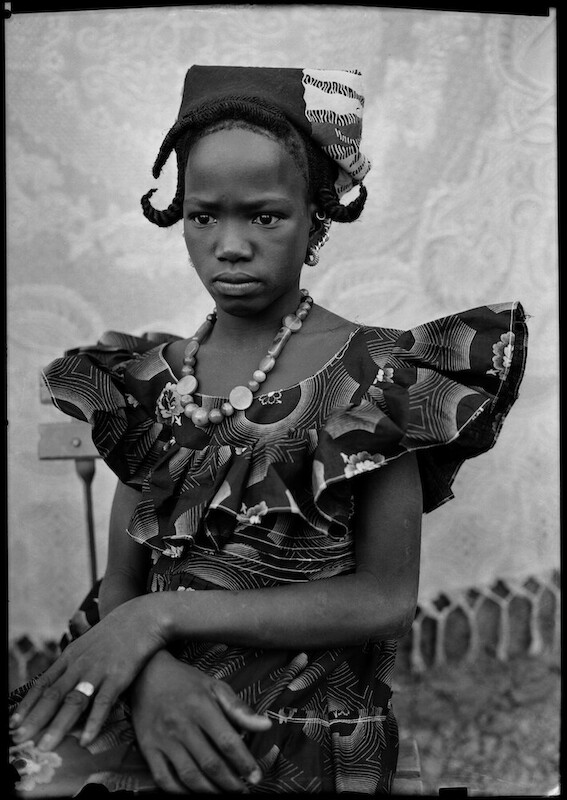

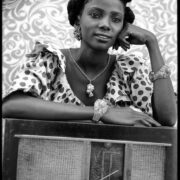

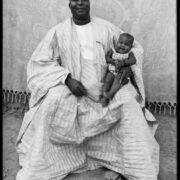

Photographs: Seydou Keïta

Text: Alexander Stuparich

Seydou Keïta was born around 1921 in Bamako, the capital of the Republic of Mali. A self-taught photographer, his portraits earned him a reputation for excellence throughout West Africa. Inventive and highly modern, his emphasis on the essential components of portrait photography—light, subject, framing—firmly establishes Keïta among the 20th-century masters of the genre.

Seydou Keïta’s photographs eloquently portray Bamako society during its era of transition from a cosmopolitan French colony to an independent capital. Initially trained to follow his father’s carpenter trade, Keïta’s career as a photographer was launched in 1935 by an uncle who gave him his first camera, a Kodak Brownie Flash, which he had bought during a trip to Senegal. During his adolescence, Keïta mastered the technical challenges of working with light and printing. After the initial apprenticeship of him photographing his family, friends, and his father’s clients, Keïta set up an open-air studio in another family’s yard, where he was renting a room.

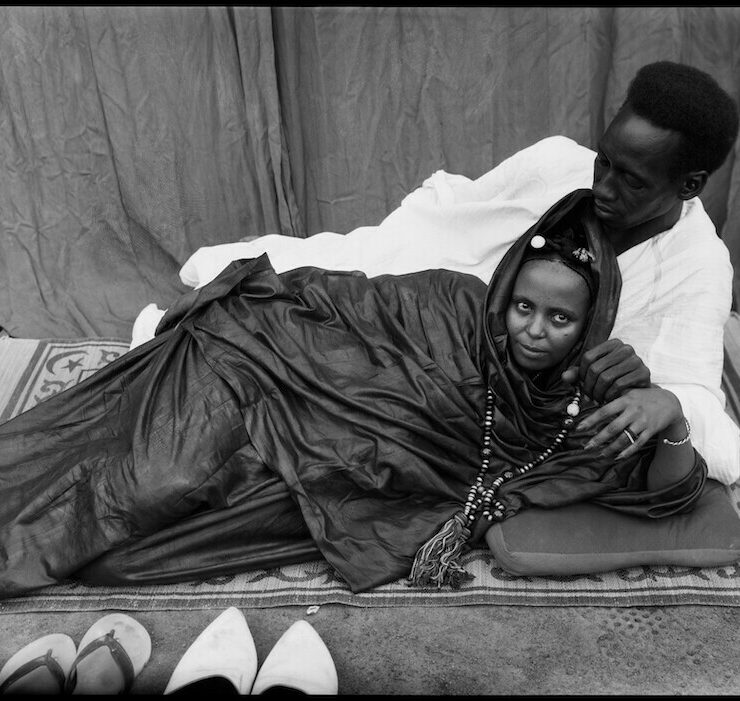

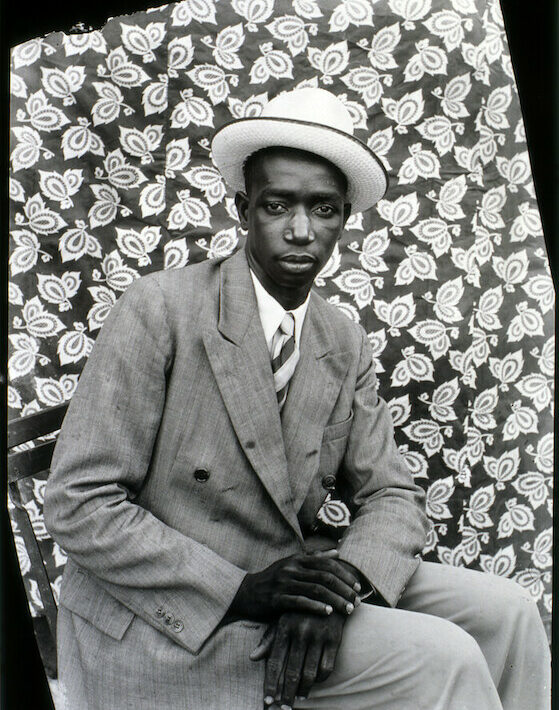

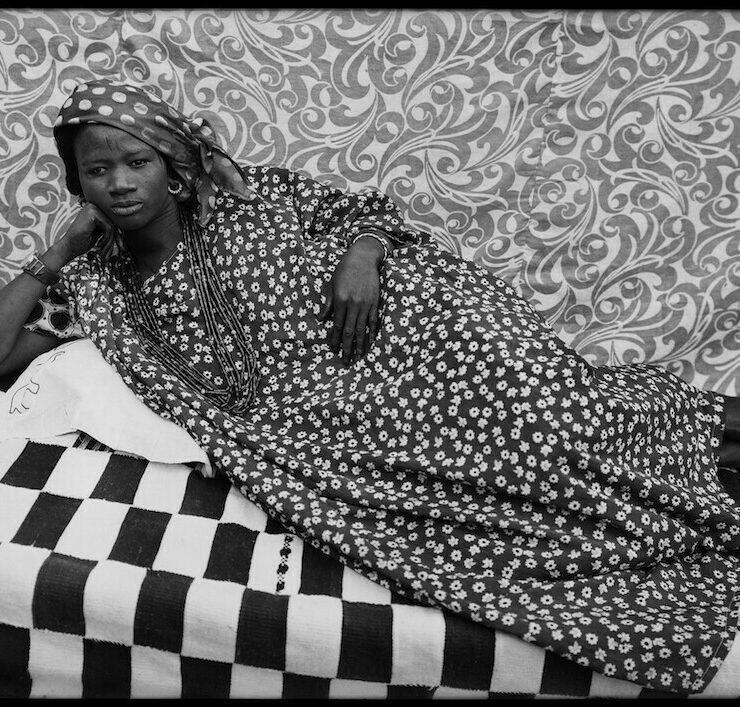

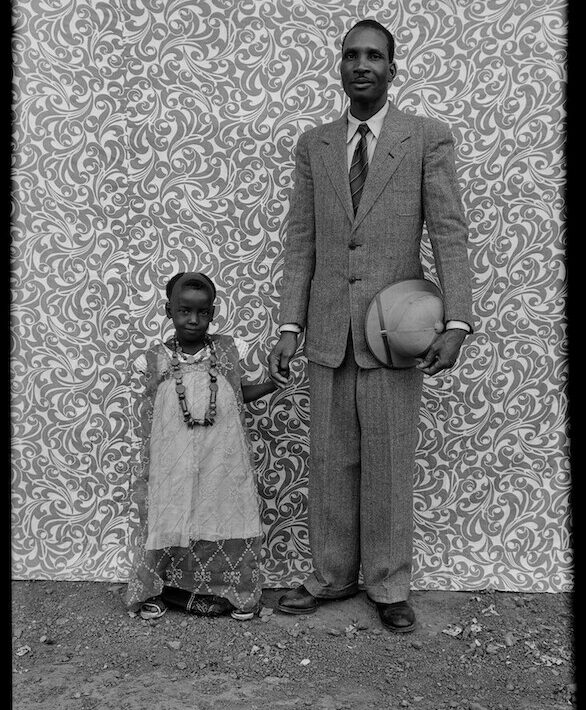

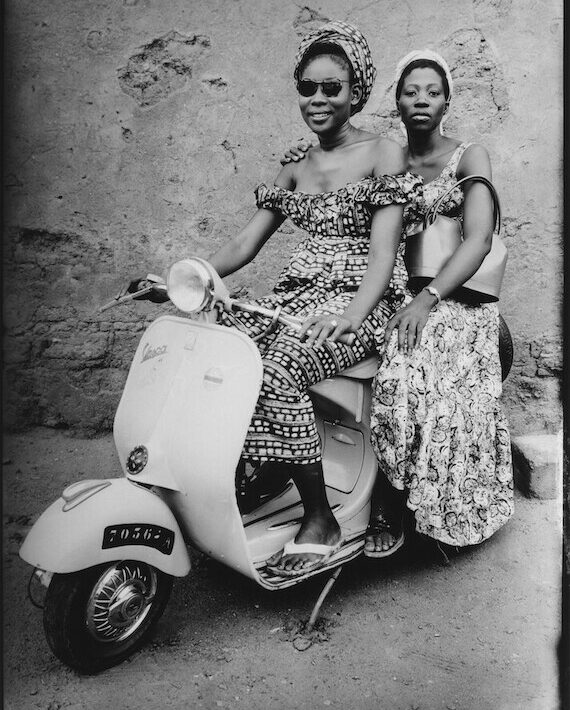

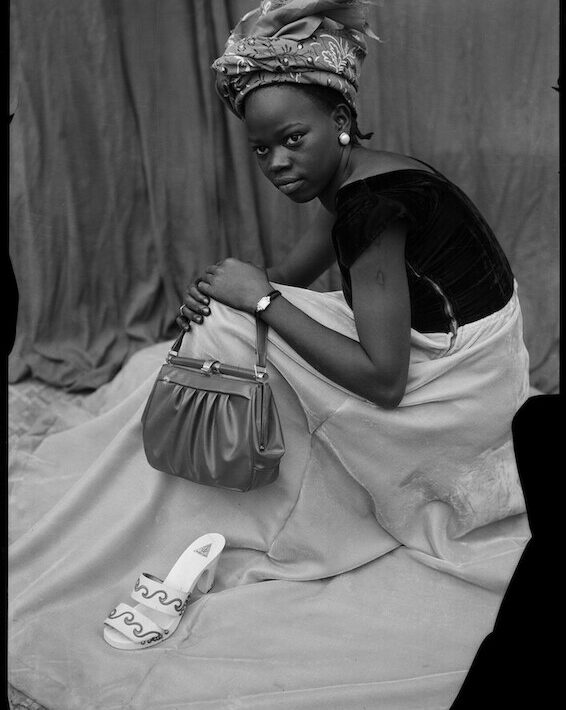

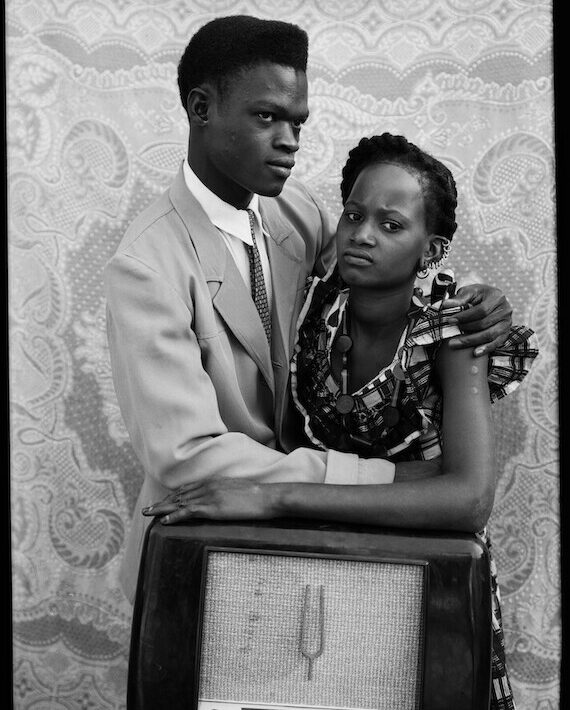

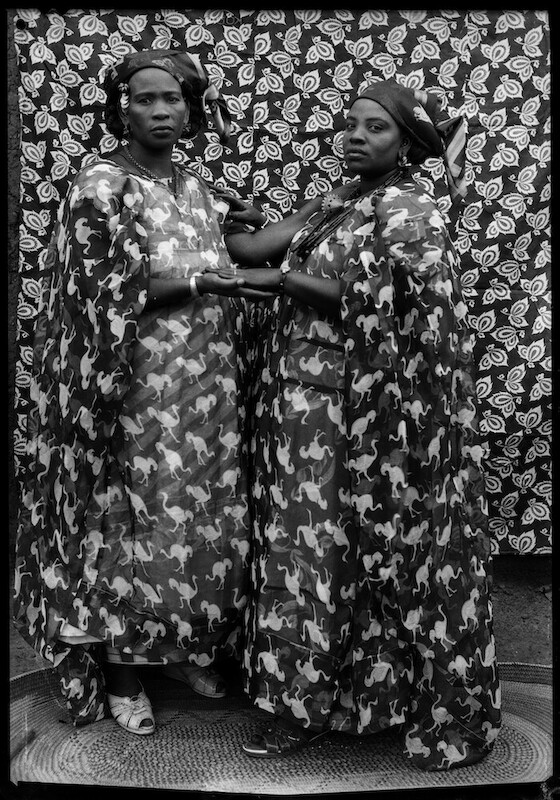

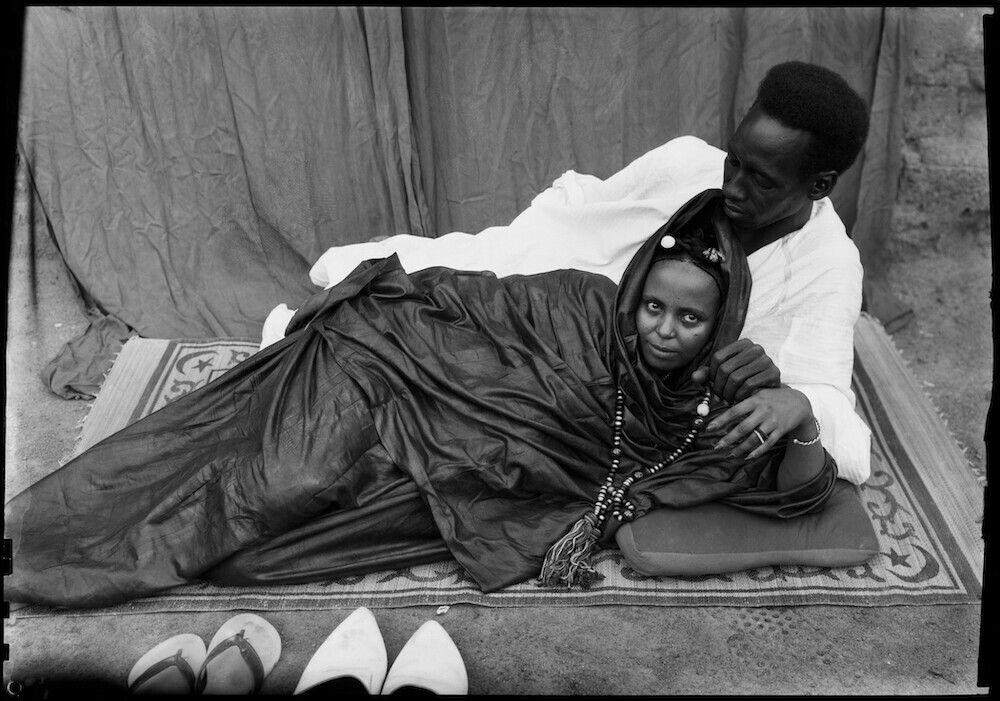

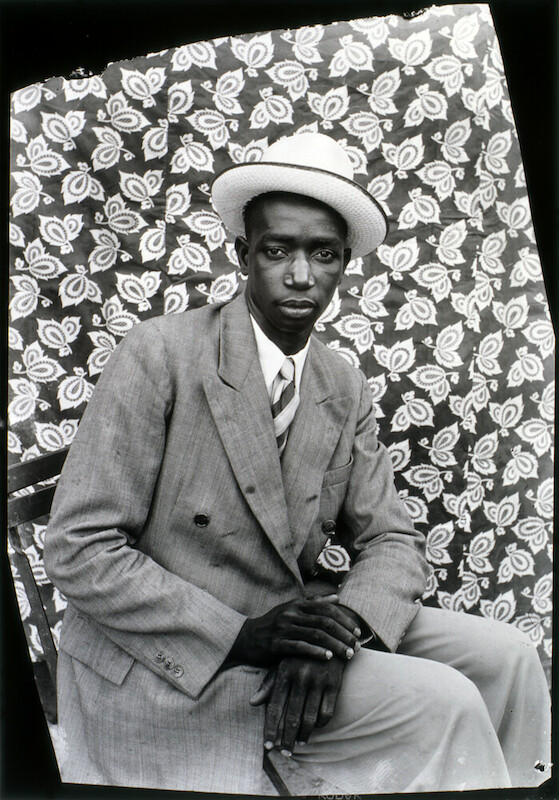

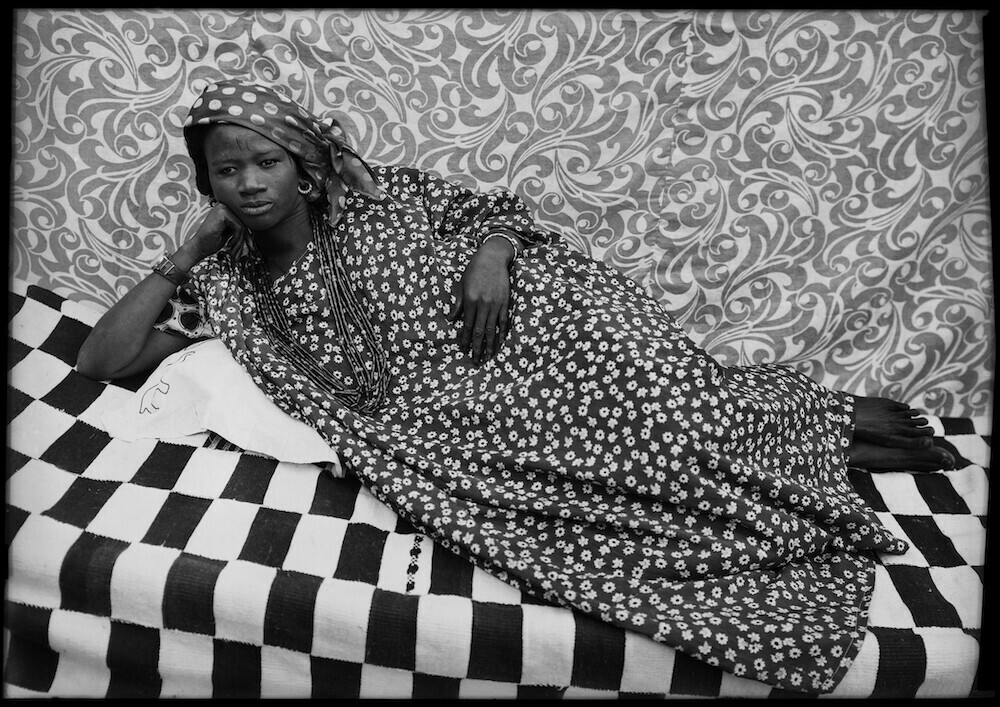

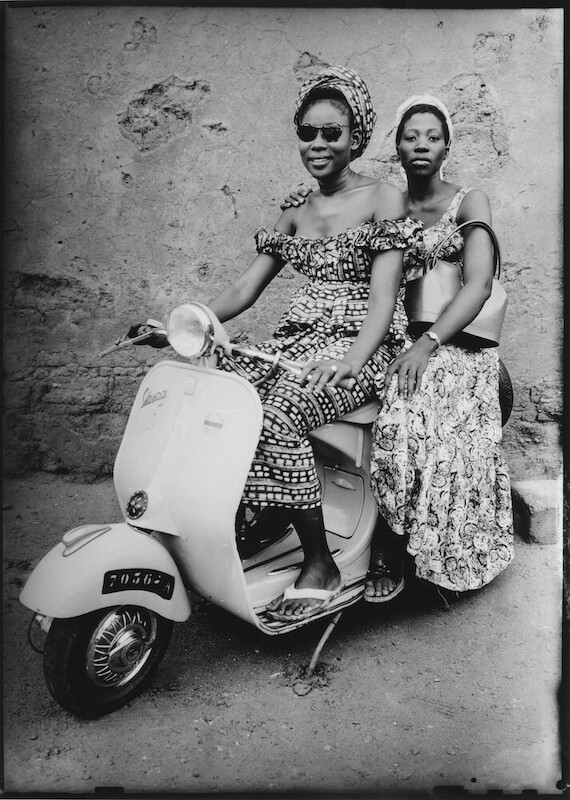

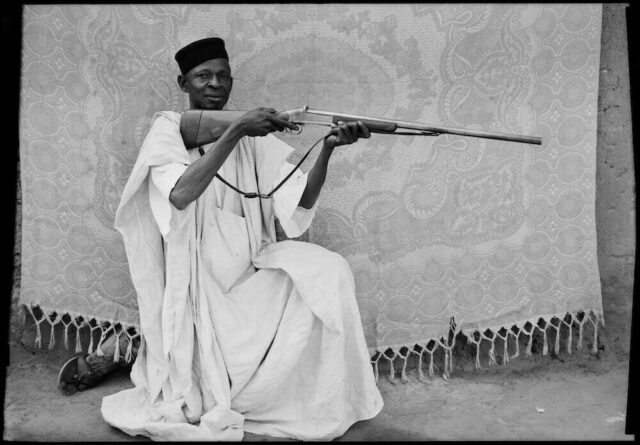

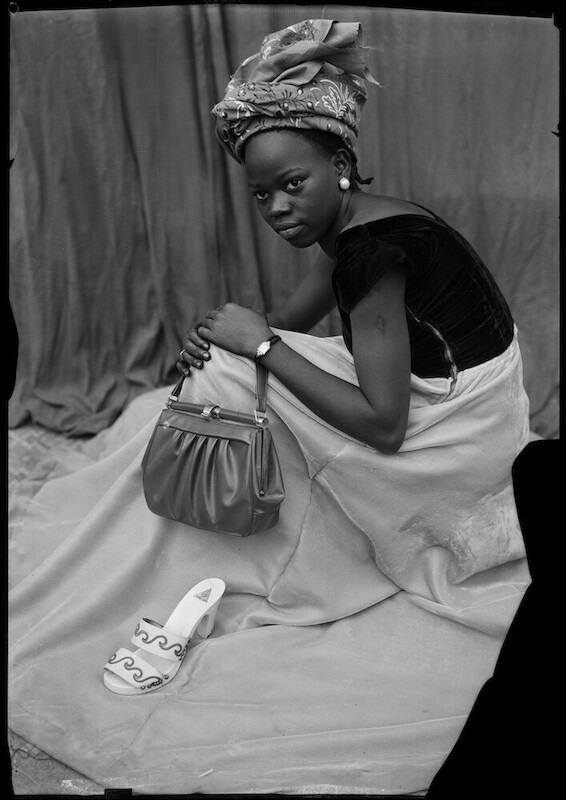

In the following decade he bought two more cameras and in 1948 he acquired a used 13×18 inch camera with a broken shutter. The larger format not only offered an exceptional degree of resolution but also made it possible for Keïta to make high-quality contact prints without the aid of an enlarger. Primarily lit by sunlight, all of his portraits from 1949 to 1962 were taken with this camera, which Keïta mastered by removing the lens cap for a precise period of time to properly expose the film. For economic reasons, he only took one shot to achieve each photograph. His numerous clients were attracted by the quality of his photographs and his great sense of aesthetics. Many were young men, dressed in European-style clothing. Some clients bought items they wanted to be photographed with, but Keïta also had a selection of European clothing and accessories that he made available to them in his studio. Women arrived in loose robes that often covered their legs and neck, only beginning to wear Western attire in the late 1960s.

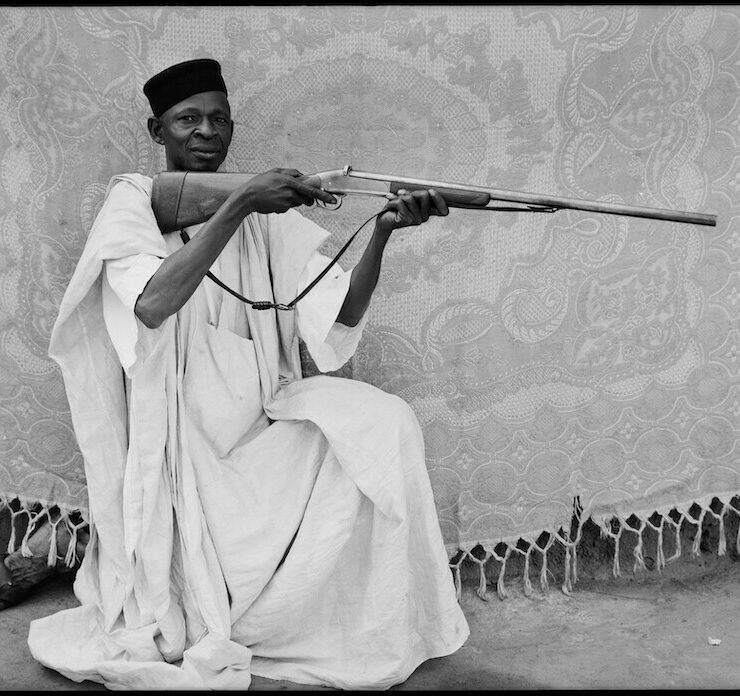

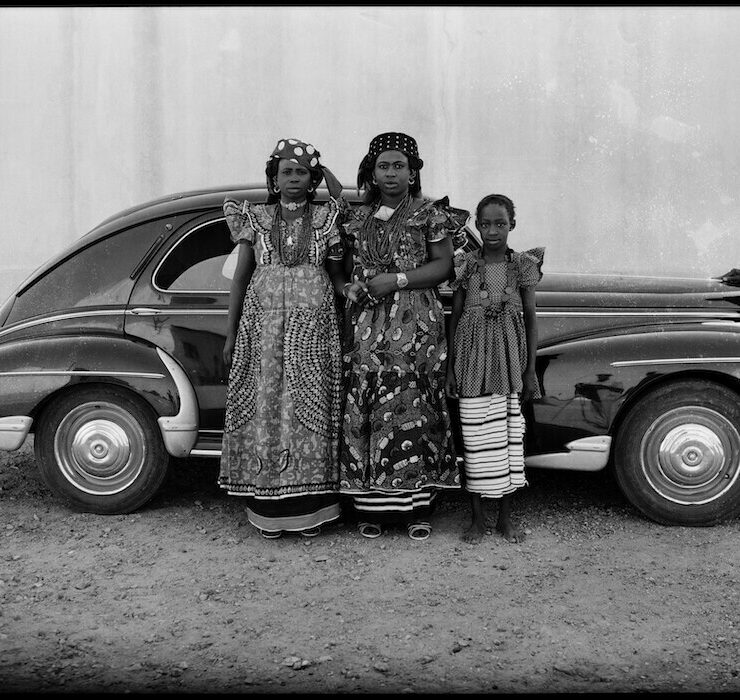

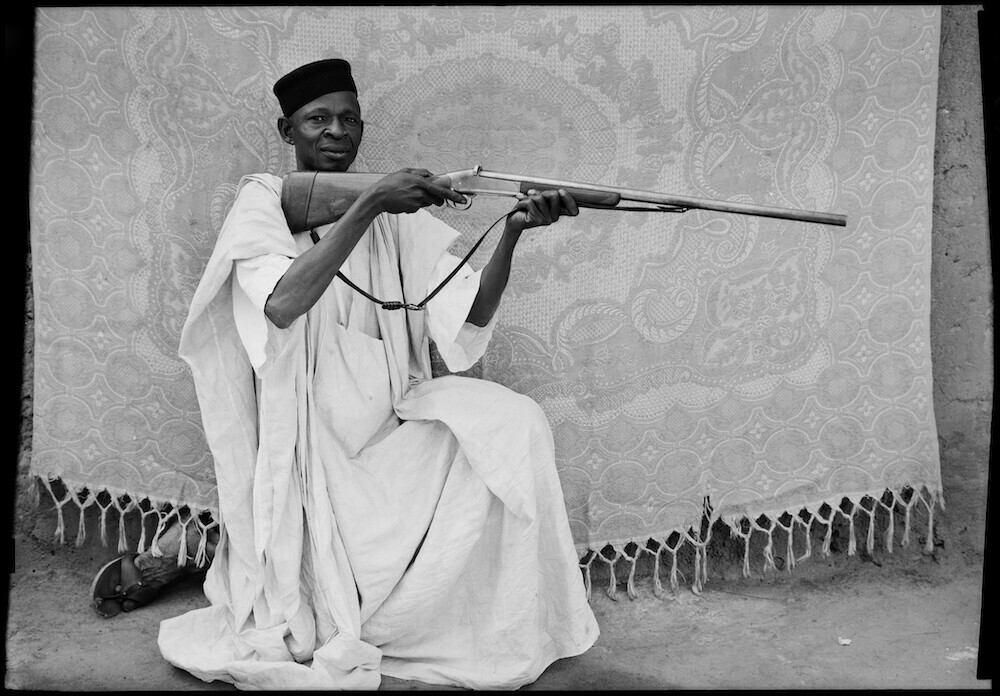

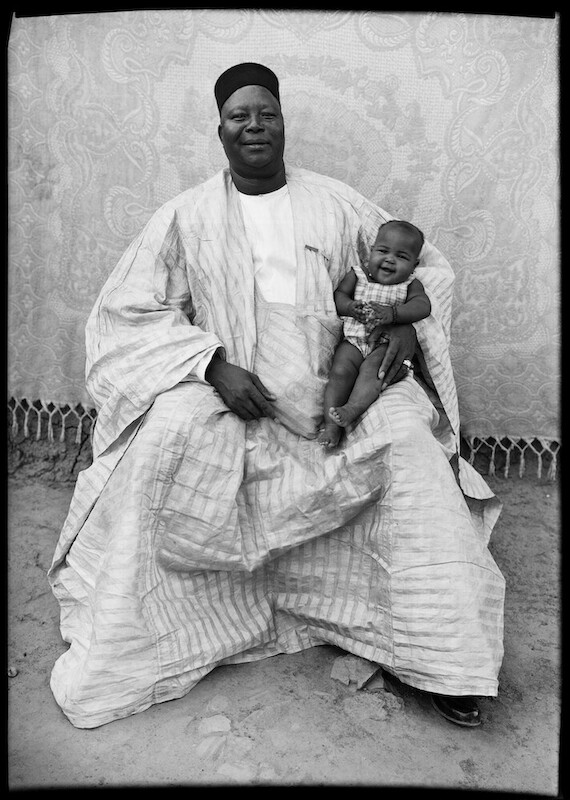

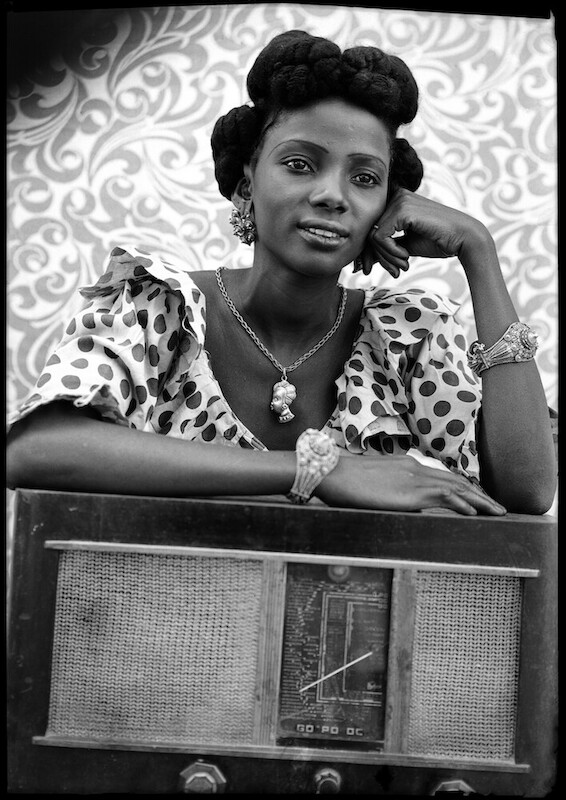

To promote his business, he stamped “Photo Keïta Seydou” on the back of the pictures and hired assistants to go looking for new customers at the nearby market and train station. By 1952 his studio in Bamako was already a successful business, establishing him as a locally renowned portraitist. Serving elite and middle-class clients, his images often highlight the idealised or imagined socioeconomic status of his models by including accessories: cosmopolitan clothing and objects, radios, telephones, bicycles, watches, pens, motorcycles, and sometimes, his own car.

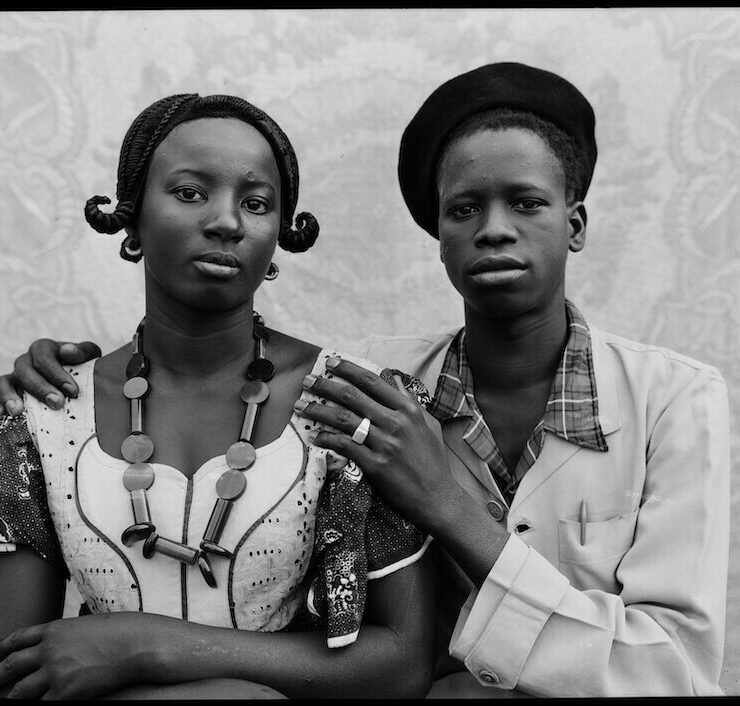

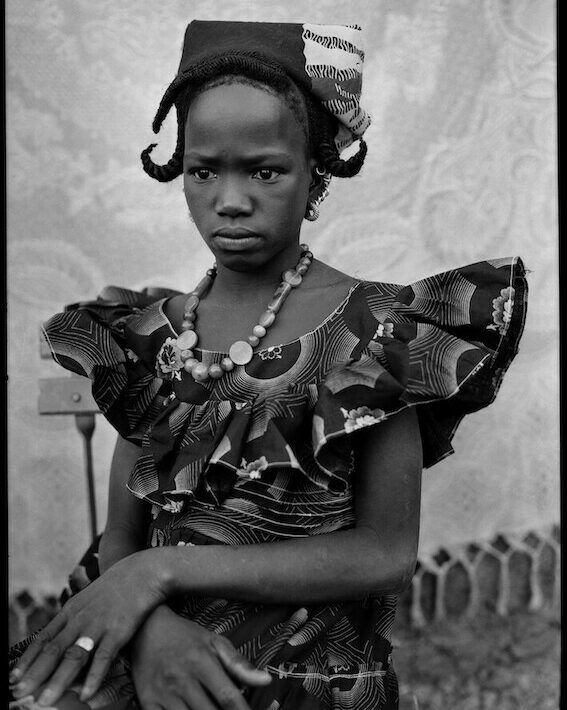

He would renew these accessories every few years, which later allowed him to establish a chronology of his work. To formalise the outdoor setting, Keïta regularly employed richly patterned backgrounds that add movement and visual energy to the images. He used a low point of view and angular composition to highlight the confident facial expressions and relaxed postures of his clients. Parallel to his studio practice, Keïta visited people’s homes to compose portraits and travelled to rural villages to take identification photographs.

The year 1960 is the end of the colonial era for the region and Mali becomes independent from France. An independent, socialist Africanist-oriented one-party state with strong ties to the Soviet Union was established, which carried out extensive nationalisation of economic resources. The newly installed socialist government appoints Keïta as its official photographer. Keïta starts working for the government and his first assignment is to take mug shots of the prisoners at the police headquarters. (These images were allegedly destroyed in a fire during skirmishes of a coup.)

Meanwhile, the study remained in the hands of his brother Lacina, his son Mamadou and the assistants Abdoulaye and Mouris. However, with the growing economic deterioration and scarcity of goods and services typical of socialism, the business faltered. When Keïta finally retired from the studio in 1977, his equipment had been stolen, prompting him to transform the space into a garage.

Seydou Keïta was discovered in the West in the 1990s. His archive of more than 10,000 negatives gradually came to light. In 1992, French photographers Bernard Descamps and Françoise Huguier, together with gallery owner André Magnin, arrived in Bamako in search of Keïta, whose work had been presented without authorial identification in the exhibition ‘Africa Explores: 20th Century African Art’ (1991) at the New Museum of Contemporary Art in New York.

The following year, Keïta’s accredited photographs were first presented to foreign audiences by Huguier and Descamps at the Rencontres internationales de la Photographie in Arles, France. Subsequently, Keïta did fashion shoots for Harper’s Bazaar and French designer Agnès b, achieving international recognition. His first solo exhibition took place in 1994 in Paris at the Fondation Cartier. This was followed by many others in various museums, galleries and foundations around the world.

Keïta’s work has appeared in numerous exhibitions, including the Guggenheim, Kunsthalle Wien, MoMA, Düsseldorf’s Kunst Palast, London’s Hayward Art Gallery, Centre Georges Pompidou, and Johannesburg Art Gallery. His monographs include Seydou Keïta (1997) and Seydou Keïta Photographs (2011). His photographs have also been presented at international festivals and biennials in Bamako (1994), São Paulo (1998), and Madrid (1999). In honour of Keïta’s lifetime achievements, the Bamako Rencontres Grand Prix is named the Seydou Keïta Award. Keïta died in Paris on November 22, 2001.

Whether photographing individuals, families, or professional associations, Keïta balanced a strict sense of formality with a remarkable level of intimacy with his subjects. On his practice in the studio, Keïta commented: “It’s easy to take a picture, but what really made the difference was that I always knew how to find the right position and I never made a mistake. The slightly turned head, a serious face, the position of the hands… I was able to make someone look really good.”

Keïta went to great lengths to bring out the beauty of his subjects and the bright patterns in his backgrounds proved to be a particularly effective contrast. He worked intuitively, reinventing portrait photography through his pursuit of extreme precision. He is now universally recognized as the father of African photography and considered one of the great photographers of the 20th century.

With biographical references by André Magnin and Candace M. Keller. Thanks to Elisabeth Whitelaw, Collection manager CAAC – The Jean Pigozzi Collection of African Art.

About the Author:

Alexander Stuparich is editor of CAPTION Magazine for North America and Asia.

Links: The Jean Pigozzi African Art Collection caacart.com