+24

+24 In the shade of Carob trees

In the shade of Carob trees

Chilex_1

En la naciente del río Salado, segundo principal afluente del Loa y cercano a la comunidad de Toconce, se erige una gran infraestructura de abducción de agua de propiedad de Codelco. Esta obra de ingeniería, que actualmente no se encuentra en funcionamiento, es parte de un complejo sistema de extracción, trasvase, canalización y almacenamiento de agua para los yacimientos mineros cercanos a Calama. © Gaspar Abrilot.

Photographs: Gaspar Abrilot

Research: Jorge Rowlands

Text: Jorge Gronemeyer

Chile is too civilized to attract the explorer, too remote to tempt the hiker, and too European to arouse the curiosity of the crowds.

We generally know the name and, in a vague way, the latitude under which this land as large as France is located, which unfolds between the Pacific and the Cordillera, from the Atacama desert, through the fields of the central valleys and jungles of Araucanía to the glaciers of Tierra del Fuego.

-CHARLES WIENER, Chili & chiliens

There are some publications from the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century that had the objective of showing the world the characteristics, potential and riches of Chile. These books used printed texts, numbers, maps, and photographic images to bring readers from other latitudes and cultures closer to our “history, people, trade, industry, and wealth,” as the subtitle of the book Impressions of the Republic of Chile stated in the twentieth century(2), printed in England in 1915.

Projecting a beautiful, orderly, safe, civilized and modern country was essential to attract and encourage the interest of investors who wanted to benefit from the riches of this prosperous territory. At that time, the main resource was saltpeter(3), used by the chemical industry to produce fertilizers and explosives. The exploitation of saltpeter was in private hands, mainly English, and the Chilean State benefited from export taxes, vigorously increasing the fiscal coffers and leading the country to a sustained –although always uneven– economic growth. This was reflected in the public works and the modernization of the nation, such as, for example, the construction of an extensive railway network, which ensured the union between various cities, and the connection of the production centers of raw materials with the ports for its export.

The world economic crisis, beginning in 1929 (known as The Great Depression), and the production of synthetic saltpeter at the end of World War I mark the end of the saltpeter era; and copper, until then the second economic activity -extracted on a large scale since the beginning of the 20th century-, became the pillar of Chilean wealth, a situation that continues to this day, being the main producer of this mineral in the world. The strategic importance of copper caused that, in 1964, during the mandate of Eduardo Frei Montalva, a process of “Chileanization” of the mineral began, where the State bought shares from foreign companies, an issue that later led to the “nationalization of copper” in 1971, promoted by the government of Salvador Allende Gossens. But the idea of nationalizing the wealth of this land was already raised at the end of the 19th century, as an attempt to retain profits in the country and limit or condition the presence of foreign capital. On the contrary, during the period of dictatorship, after the coup d’état of September 11, 1973, a “denationalization” of resources was imposed, an issue that was perpetuated in all the governments that succeeded the dictatorial period.

A fundamental part of the political and economic history of Chile happens, or is related, to the northern part of this country, where the Atacama desert is located. It is precisely a disagreement related to saltpeter taxes that triggered the armed conflict with Bolivia and Peru, known as the War of the Pacific or War of Saltpeter (1879-1884). After the war, after a series of treaties and pacts, Chile annexed the province of Antofagasta, belonging to Bolivia, to its territory; and the provinces of Tarapacá and Arica, belonging to Peru, thus monopolizing the production of saltpeter.

The Atacama Desert, which encompasses the regions of Arica and Parinacota, Tarapacá, Antofagasta, Atacama and the north of Coquimbo, is considered the driest territory in the world. The Loa River, which crosses this desert from the mountain range to the sea, was the border between Peru and Bolivia before the War of the Pacific. It is located between the current regions of Tarapacá and Antofagasta and, with its 440 kilometers, it is the longest river in Chile.

This is part of the territorial and historical context necessary to understand this project, made up of photographs, research, documents, texts, exhibitions and publications. To address this immense and arid area in depth, it is necessary to understand the particularities of this territory, with its extreme geography and climate, as well as the vulnerability and tensions of this natural landscape in relation to its inhabitants in different temporalities and circumstances, the environmental disasters resulting from the extraction of its mineral resources, in addition to the various layers that make up its complex history.

The publications alluded to at the beginning of this text (Chili & chiliens and Impressions of the Republic of Chile in the 20th century), had a clear propaganda purpose, where the already exploited resources were presented and, in some implicit way, the resources to be exploited. The natural riches, which seemed inexhaustible at that time, were related to the idea of well-being, prosperity and development. This is reflected in the last lines of the prologue of the aforementioned book Impressions of the Republic of Chile:

“Finally, the editors of this volume allow themselves to hope that the effort made to do justice to the amazing progress of Chile and the wonderful vitality of its soil will contribute to channeling the capital and labor necessary to consolidate prosperity and world prestige of the Republic”(4).

In the shadow of the carob trees, after a little more than a century of what was previously reported, connects us with the events related to this territory, from a critical, ecological point of view, vindictive of its inhabitants and, in particular, with the ancestral peoples who inhabited and inhabit this region. But what it cannot do is illustrate the words quoted from the prologue, because those expectations and hopes were simply not fulfilled or directly affected only a small and privileged elite, who grossly enriched themselves at the expense of exploiting workers and violating the vital rights of the original inhabitants of those lands.

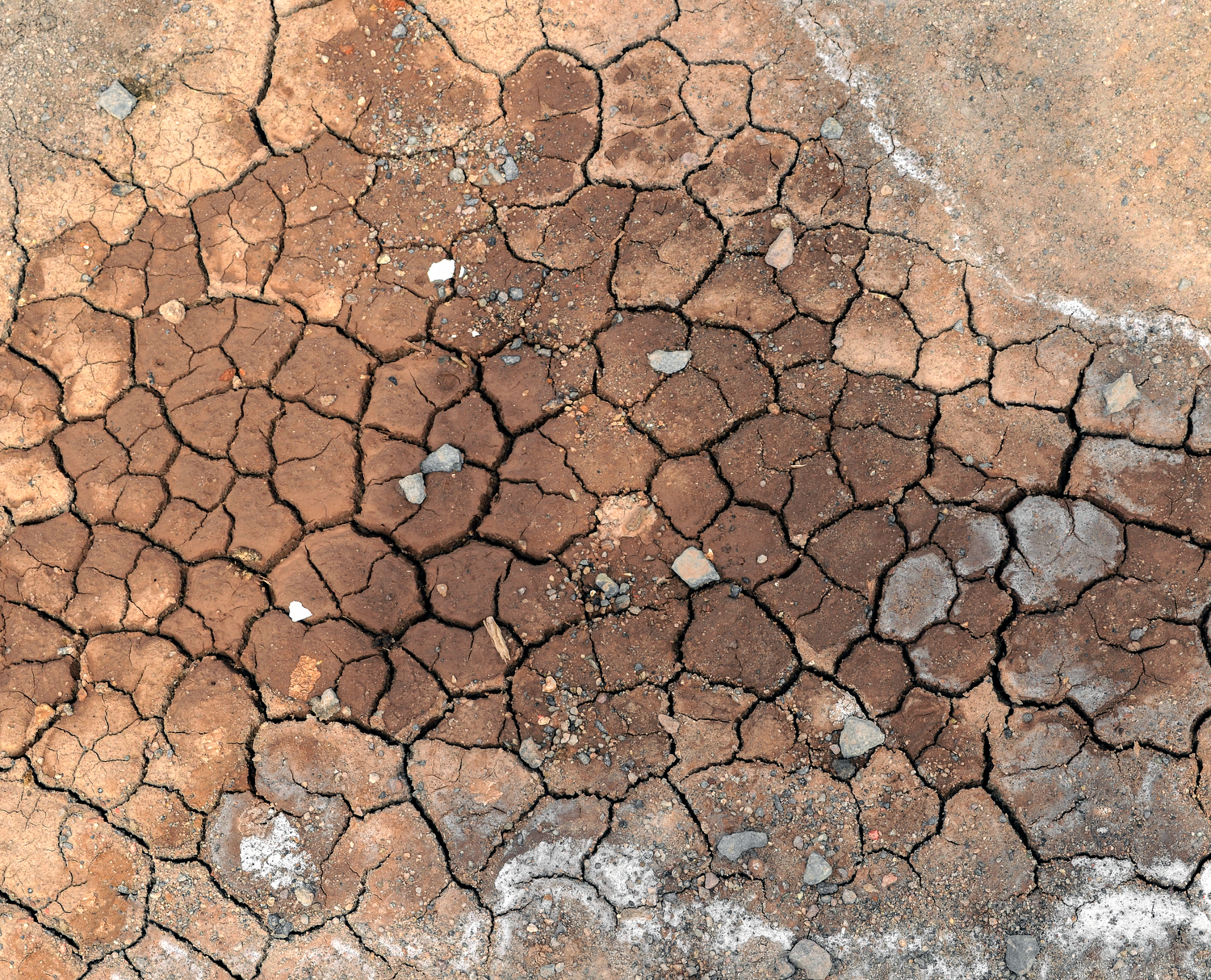

Photography once again shows us the inescapable beauty of the environment –that is inevitable–, but this time it points to and makes visible in its discourse the fragile and precarious balance of this territory and its inhabitants. The natural scarcity of water, typical of an arid zone, is added to a historical and unlimited voracity of the extractivist industry, which in its operations diverts, towards its own and particular use, the water available for human consumption. The pipes that carry water to the mines intervene in the landscape, just as the horizon is fragmented with veritable mountains of waste material from mining operations, polluting the environment and becoming true monuments to impunity and absolute disregard for the environment. The immense exposed surface of the desert reveals the changes in the landscape, the traces, the scars of various temporalities. Everything is exposed, the landscape is an open book to the verification of the barbarities that have been committed there, both in environmental and human aspects.

Written and oral accounts of bloody events overlap one another. From the atrocities of the War of the Pacific to massacres of workers, such as the one that occurred in the Santa María de Iquique School in 1907, or the Chacabuco political prison camp, located there only two months after the civic-military coup led by Augusto Pinochet in 1973, in what used to be a saltpeter office, active between 1924 and 1940 and converted into a national monument in 1971. But the numerous cases that have affected locals in reference to contamination and access to water are also extremely violent and systematic, such as for example, what happened in the oasis of Quillagua, located in the municipality of María Elena, on the banks of the Loa River. In 1911 the construction of the Sloman dam was completed, a hydroelectric dam, currently in disuse, which fed energy to the mining activity, considerably altering and reducing the course of the Loa River. All this, exactly in the sensible driest point of our planet.

It is important to reflect on these historical and current social, economic, environmental and cultural problems, exposed almost as an example in the territories that constitute the great north. Especially now, in the context in which the Constitutional Convention works presenting, analyzing and voting on norms that will build the new Chilean Constitution. This process is seen by some people as a sort of refounding of the country, where important matters such as, for example, establishing that Chile is (or, rather, will be, depending on the results of the exit plebiscite) a Regional, multinational and intercultural state. Or essential aspects, such as access to water being enshrined as a human right(5), in addition to a series of regulations aimed at dealing with climate change and environmental problems in general. This occurs at a crucial moment, at a turning point in terms of an ecological and sustainable notion, after a long period in which these conflicts were not an issue simply because they hindered or slowed down the petty interests of a few. In this context, a theme that resonates strongly is the nationalization of Chile’s natural assets, such as copper and lithium, establishing a role for the State in mining and the coexistence of this productive activity with due respect and care for the environment, and incorporating the voice and participation of indigenous peoples.

History continues to be written, events sometimes take place imperceptibly in an apparent and immovable status quo and, at other times, like the current one, they become more dynamic as a result of a long period of stagnation, disenchantment, of suffering abuses where impunity is normalized and heightened despair. How not to think about the “social uprising” of October 18, 2019, which was the impetus for profound transformations in Chile, where a significant percentage of the population urgently demanded and required a change in the system. This work is in that line: it is postulated, developed and specified with a critical spirit of what we have built as a country. How not to condemn the fact that the territory covered by In the Shadow of Carob Trees is, on the one hand, the most economically productive, and on the other, it is among the poorest and most precarious regions of the country. Chile has the world’s largest reserves of copper and lithium, critical minerals in clean energy transitions. We hope that this will become a new opportunity to materialize that promise of prosperity, but that this time it benefits our entire society across the board.

1 Wiener, C. (1888). Chili & chilies. Librairie Leopold Cerf.

2 Lloyd, R. (1915). Impressions of the Republic of Chile in the twentieth century. W. Feldwick Publishers.

3 Saltpeter is a mixture of potassium nitrate (KNO3) and sodium nitrate (NaNO3).

4 Lloyd, R. (1915). Impressions of the Republic of Chile in the twentieth century. W. Feldwick Publishers.

5 Currently, only 53% of the rural population has access to drinking water through a public network, the rest of the population is supplied through other sources, such as wells, waterwheels, rivers, estuaries or cistern trucks. (Rivera, D., Donoso. G, Molinos, M. (2021, November 8). Human right to water: necessary clarifications for its consecration and fulfillment. Diario El Mostrador).

Exhibits

In the shadow of the carob trees will be presented thanks to a series of national exhibitions: Sala Chela Lira de Antofagasta (August 2022), Centro Cultural La Moneda, as part of the exhibition Expediciones (August 2022), Sala Tierra del Fuego , Punta Arenas (December 2022), Pinacoteca de Concepción (March 2023), Laboratory Room, Valparaíso Cultural Park (July 2023)

About Gaspar Abrilot

Born in Santiago de Chile, Gaspar is a professional photographer and holds a Master’s degree in photographic research and creation from the Univ. Finis Terrae. His authorial work has been developed analogically around environmental documentary, focusing mainly on landscapes altered by human beings. From this discipline he seeks to highlight the different social, political or geographical realities of areas that have undergone a transformation as a result of the indiscriminate intervention of the individual.

Professionally, he is an editor and printer at the prestigious Gronefot Fine Art / Sala de Maquinas workshop, where he works on color management, digitization, restoration, and preparation of photographic archives for institutions, museums, and prominent national and international photographers. He is also a professor at the Andrés Bello University and the University of Talca and has made important contributions in the rescue of photographic heritage for the National Library, La Moneda Palace, the Vicuña Mackenna Museum, the Maipú Museum, the SudFotografica Foundation and the Víctor Jara Foundation.

Winner of four Fondart scholarships, he was part of Young Emerging 2014 and his work has been exhibited in various photography magazines. In Chile he has participated in group exhibitions at the Palacio La Moneda Cultural Center, Pinacoteca de Concepción, Pablo Neruda Hall in Santiago, Chela Lira Hall in Antofagasta, Mapocho Station and the former Prison Cultural Park in Valparaíso. Internationally he has been invited to the visual and anthropological meeting ALA 2020 in Montevideo, Uruguay; Equinox Fair in Brazil and the PhotoPatagonia, Río Gallegos (2016 and 2018) and Infoto 2020 festivals, Buenos Aires, Argentina. In 2021 he was awarded first place in the environment category at the 42nd National Photojournalism Hall.