+44

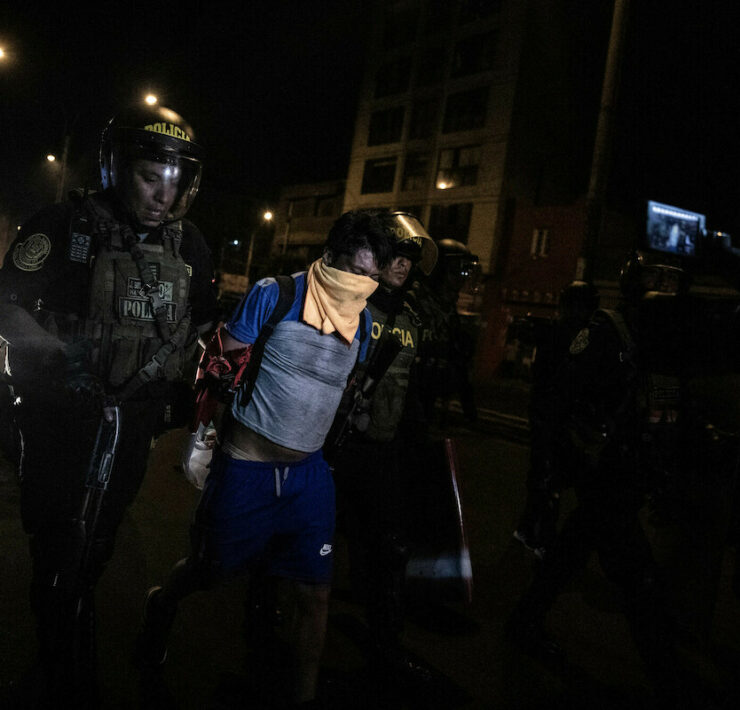

+44 Images of the crisis in Peru

Demonstrations in Peru have been extremely violent, with more than 60 dead. In a single day, at least 17 deaths were recorded in the south of the country, while secessionist initiatives of some groups that propose that the south of Peru separate as an independent state grow.

Images by Sebastian Castañeda

Text by Alexander Stuparich

Democracy in Latin America is going through one of its most delicate moments, with its counterpart at the hemispheric and world level. Peru is suffering a very serious crisis, which in comparison turns the 2019 outbreak in Chile into a kind of peaceful demonstration.

At such a critical moment in the history of politics and democracy in Peru is the until recently Vice President Dina Boluarte, a member of the Peru Libre party, the same party as deposed Pedro Castillo.

The Peruvian Constitution allows the Balkanization of political parties, which has resulted in some twenty parties without a reasoned political position but rather absolutely conjunctural. At the top of this conjuncture party is Vladimir Cerrón, whose lawsuits prevented him from being the presidential candidate in the last elections.

Analysts indicate that Cerrón, an ideologically Castroite politician, is therefore anti-systemic and when it happened that despite the very weak candidate Castillo conquered the government, he entered the system. From this perspective, what Pedro Castillo did with his self-coup attempt and under Cerrón’s directive is, to his own detriment, complying with blowing up the system that had made him president. The person who succeeded him in the same line, Vice President Dina Boluarte, discovered that if she followed this process, what would trigger in Peru was not a replacement system, but rather a vacuum.

Unlike Sebastián Piñera in Chile, Boluarte did not hesitate to call on the legitimate force of the State, exercised by the police and the Armed Forces.

Peru has a powerful police and Armed Forces that are somewhat different from those of other Latin American countries due to a certain balance from the point of view of its combat morale, in addition to having entered positively into the popular psychology of its country at the time. of the war for its heroism in annihilating the Maoist guerrillas.

On the other hand, one of the undeniable current phenomena is the open intervention of foreign rulers in foreign sovereignties. In the case of Peru, there is the agitation carried out by former Bolivian President Evo Morales, whose “refoundation with plurinationality” failed with the rejection of the proposal for a new Chilean constitution, so his new focus is Peru.

Morales has carried out an indirect approach strategy with his Runasur geopolitical project, for the integration of indigenous peoples, based in Cuzco, the emblematic capital of the Inca empire.

This personal foreign policy to divide Peru, whose script is very similar to the one we met in Chile (the same slogans, the same calls to burn everything, “the one who dances passes”, violence in the streets that Peruvian journalism calls peaceful demonstrations) led to Dina Boluarte prohibiting Morales new entry into the country.

In this kind of magical surrealism, Dina Boluarte first proclaimed that she was going to arrive to complete the term of Pedro Castillo, which meant elections in the year 2026. The events that took place forced her to affirm that she was going to prepare the institutions to convene a elections in 2024.

In what CNN calls a response “with the carrot and the stick,” apart from advancing elections, her Defense Minister, Luis Alberto Otárola, declared a state of emergency and deployed troops to the streets.

In January 2023, the Institute of Peruvian Studies (IEP) compiled the first public opinion poll on Boluarte. The results indicate that 71% of those surveyed disapproved of Boluarte and 19% approved of her, while 80% of those surveyed did not agree with her assuming the presidency.

Regarding the actions of the forces of order, the majority (58%) believe that there were excesses, but the public is also very critical of actions such as the seizure of public buildings, airports or attacks on the forces of order. The Peruvian Congress, with a key role to play in ending the crisis, had the approval of 9% of those surveyed.

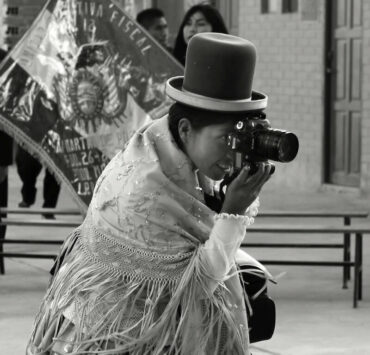

About Sebastian Castañeda:

Sebastián Castaneda was born in Lima in 1970. He graduated from the Law School at the University of Lima in 1999 and since 2002 he has been dedicated to photography.

Working as a photojournalist at El Comercio until 2014. Sebastián has done assignments throughout Latin America, as well as in Canada, USA. In the Middle East he has covered Syria, Lebanon, Turkey and Iraq. He currently collaborates with the news agencies AFP, AP, EFE and the Turkish Anadolu Agency.

He covered the war in Iraq in 2014, the armed conflict in Syria in 2013, Lebanon in 2013, the 2012 elections in Venezuela, the funeral of Hugo Chávez in 2013, the Dakar Rally in its 2012 and 2013 editions, the 2007 earthquake in Peru, the 2010 Chile earthquake, the 2016 Ecuador earthquake, voodoo ceremonies in Haiti in 2010 and 2011, Occupy Wall Street in New York in 2011, terrorism in Peru, the procession of San Lázaro and the social situation in Cuba and the pilgrimage of the Captive Lord of Ayabaca in Peru.

Website: