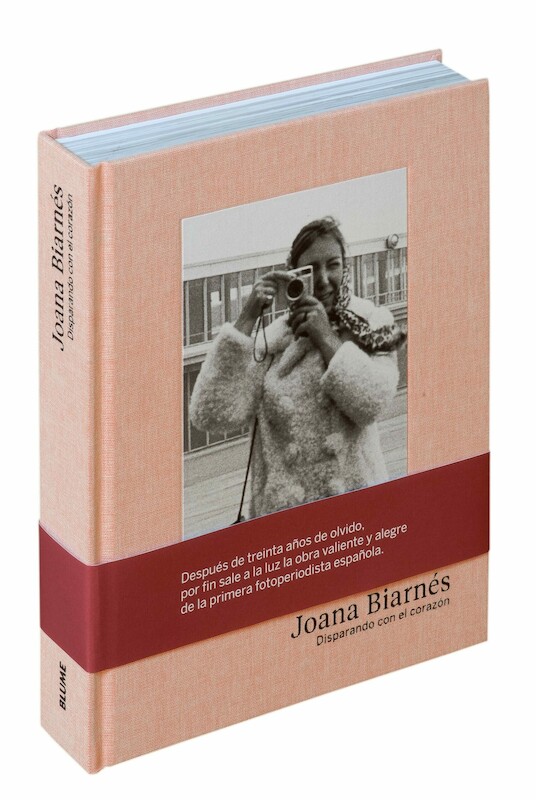

This book, published in 2017, reviews from the perspective of those who have known her throughout her life -and also her own- the process that led the Spaniard Joana Biarnés to become a renowned photojournalist. At CAPTION we reproduce some passages of this journey. It shows us how the excellence of her work, her audacity and the defense of her convictions led her to open a space in a world that until then was only male domain.

Of Juana Biarnés and her passions

by Chema Conesa

Sometimes press photography discovers, among its professionals, narrators with their own point of view who end up giving their photographs a personal expression beyond the strict function of truthfully documenting a fact. We have always known that a good photograph is the result of aligning the eye, head and heart on the same plane, but in the case of Juana Biarnés I am not sure if these three principles are expressed in the correct order.

Juana Biarnés did not even want to be a photographer, she wanted to be a telephone operator; but hers was an effort not to disappoint her beloved father, the sports photographer Juan Biarnés, light and guide of her ethical commitment to the trade.

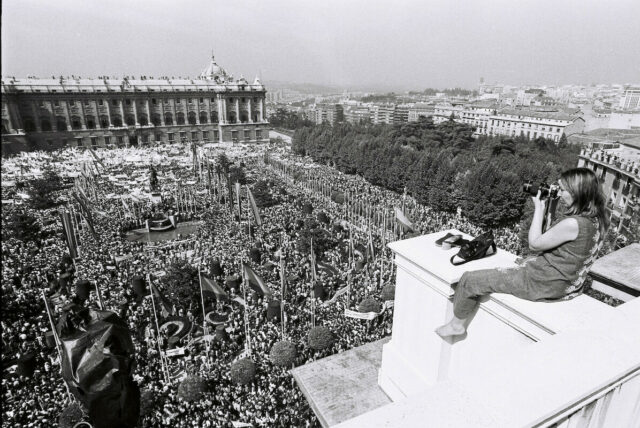

Her intuition and her good head led him not to masculinize her photography, her competence was not the value of the first line or arrogance, but her sensitivity and empathy for everything human. Her manner brought a new and unknown closeness in the press of the time, a restless look determined not to solve the play at the first shot, to follow, surround, discover the crack that allows access to the heart and obtain an apparently simple record. The excellence of avoiding the superfluous. The aim of hitting with the look. The communication itself. Her determined spirit and her will not to hide her feminine side served her to dress up as a candid blonde, when the occasion required it, to break down walls and get information where it was not easy to obtain it.

One among them

by Natalia Figueroa

This is how I see it as I write. Flash back. Juanita, Juana, Joana. Different stages of her life. She was among them all. She closed her eyes and there she was. With her cameras hanging around her neck, her blonde hair, her silk shirt (natural, always), her joy of living, her strength, her sense of humor, her enormous personality. Eating the world. They recriminated her that it was a place for photographers. “I’m a photographer,” she told them. “This is a man’s job, honey!” She yelled at them. How many times this chorus, Juana? And the funny thing is that she had never been fond of photography. She wanted to be a telephone operator although she was fascinated by her father’s laboratory. It was a world apart. She always wanted him to be proud of her. And she made it. Her father adored her. Her teacher.

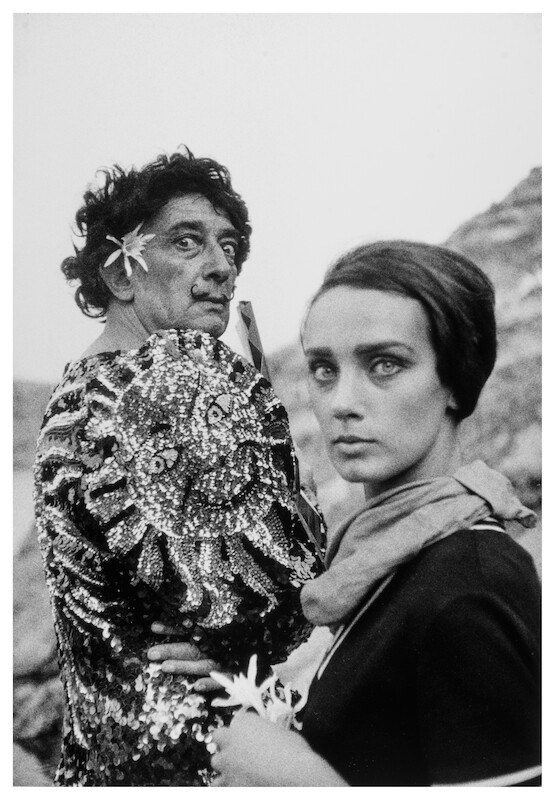

In September 1962, a terrible flood devastated the Vallès region. She helped her father cover up the tragedy. It was a brutal impact. In Pueblo she would become the first Spanish woman photojournalist. A journalism school where they competed in a friendly atmosphere. Mythical Pueblo, with Emilio Romero at the helm. And with Juan Luis Cebrián, Tico Medina, Raúl del Pozo, Antonio Olano, Jesús Hermida, José Luis Balbín, Jesús de la Serna, José Luis Navas, Vicente Talón, Yale, Manuel Molés… And her among them all. Few escaped her camera: Orson Welles, Buñuel, Nureyev, Polansky, Audrey Hepburn, Raphael, Serrat, the Beatles, Jackie Kennedy, Ava Gardner, Salvador Dalí, El Cordobés, Romy Schneider, Lucía Bosé, Tom Jones… But also the fishermen of the port of Barcelona, the old men playing cards or the saffron gatherers, the miners…

The arduous path of a pioneer

by Jordi Rovira

Joana Biarnés i Florensa, born in Terrassa in 1935 into a working family, was never a good student. “She’s very smart, but she gets distracted by anything,” the teacher told her parents. In the midst of that sea of doubts, she thought that perhaps she would be excited to be a telephone operator. The figure of Joan Biarnés, her father, was key in those hesitant beginnings. He was a renowned photojournalist, sports correspondent in the Vallès region for publications such as El Mundo Deportivo, Destino, As, Lean or Vida Deportiva for whom he covered cycling, football and, above all, field hockey competitions.

On Sunday, January 18, 1953, a group of seven cave exploration enthusiasts, following the instructions of a local shepherd, headed towards a crack in the Sierra de l’Obac massif, in Sant Llorenç de Munt (Barcelona). Once there, Llest (Ready, in Catalan), one of their dogs, entered the cave. The hikers followed. That crack led to a 58 meter deep chasm, where they discovered a large interior room with a spectacular set of stalactites and stalagmites hitherto unknown. That had to be made known, so two weeks later they went to Joan Biarnés’s house to invite her to accompany them the next day to return to the abyss and immortalize it. But she told them that, much to her chagrin, it was impossible because she had to cover a bicycle race first thing in the morning. Joana, who was 17 years old and had only helped her father in the photography of weddings and communions, felt bad that those people, so excited about that discovery, did not have good snapshots of the chasm. So when they were about to leave, she offered. “Come and get me, I’ll go with you,” she told them.

Joana had borrowed from her father a Leica and a Blaupunkt flash, which weighed more than three pounds. Once in the crack, she hung from a rope with the rest of the hikers. And down there she took the pictures. When her father saw them she was about to cry with emotion. On February 6, 1953, El Mundo Deportivo, a reference newspaper in Catalonia, published a report on the discovery of the abyss and illustrated it with one of Joana’s images. Her photographs caused her not only to be excited to see her name in a large-circulation newspaper, but also to glimpse, at last, an incipient professional career.

She finally knew what she wanted to be. Photojournalist. And for this, she began to accompany her father on weekends. Both formed a unique team in the 1950s and 1960s… Over the next eight years, she alone in El Mundo Deportivo signed a hundred reports. At first she signed “Biarnés, hija”, although shortly after she would sign “Juanita Biarnés”, which reinforced her own personality and ceased to be, at least at the level of authorship, a complement to her father. The images of the time show that teenager with her skirts on the soccer fields. At no time did she consider giving up her femininity to better adapt to that world of men.

Joana’s father was not the only one from whom she learned the art of photography. A young photographer, Ramón Masats, who developed in Joan Biarnés’ laboratory, also had a part of her influence. Joana and he would go some Sundays to photograph together. To the port of Barcelona. To the people on the street. The first thing that caught their attention. These were photos of a costumbrista character.

If she started in that world with the support of her father, Masats would do it in a very different way. The first camera she had was a Kodak Retina, German-made and affordable, and he bought it for her at the age of 22 after, little by little, he kept the money that her father gave him for errands. Masats never told him.

She settles in Barcelona

While studying at the Official School of Journalism she traveled daily to Barcelona by train, but once she finished her academic training, which allowed her to obtain the official press card, she proposed to her father to go live in the Catalan capital.

Once in Barcelona she rented a small studio on Calle Madrazo, in the Sant Gervasi neighborhood. Ingenuity compensated for the lack of space and she installed the developing laboratory inside a wardrobe.

In 1961 she moved to Madrid to cover the second edition of the Six Days of Madrid, a track cycling race. The presence of a sports photojournalist did not go unnoticed by Pueblo reporters. Back then, her business card was already a statement of intent. “Juanita Biarnes. Sports graphic reportero”. She defined herself as masculine because she wanted to occupy a space that until then had only been controlled by men. In Pueblo she did an interview that was published on November 9 of that year. «We present Juanita Biarnés. Although it is hard to believe, she is one of the best photojournalists that Spain has», she read at the beginning of the text.

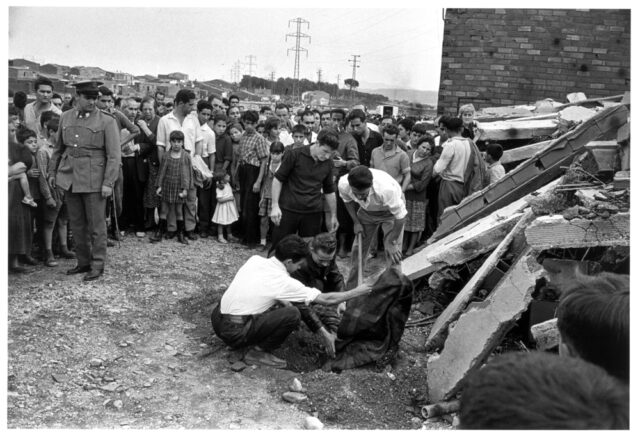

The drama of the floods

On the night of September 25, 1962, the Catalan region of Vallès experienced one of the worst natural disasters in Spain. Some floods, the result of brief but intense rainfall of up to 215 liters per square meter, left almost seven hundred dead, although some sources raised them to a thousand. The water swept away everything in its path, from the railroad tracks to houses and cars.

That September 26, Joana photographed the drama of her neighbors, of the people with whom she had grown up. In her images, corpses were seen, expectant citizens before the discovery of more lifeless bodies, families that had lost everything. More than four thousand people lost their homes. Not to mention the debris.

Her photographs reached the hands of Federico Gallo, a journalist from the Miramar studios of TVE in Barcelona, and allowed to illustrate the news of that drama. They were also published in the weekly news magazine Porqué.

Photojournalist in Pueblo

Pueblo was the official organ of the Vertical Unions. It was an evening newspaper with editions in Madrid, Barcelona, Seville, Bilbao and Zaragoza, a large newsroom, initially on Calle Narváez, later on Calle Huertas, and with many readers. In the 1960s it sold almost 200,000 copies a day, which made it one of the most widely distributed newspapers in Spain. Its reading was enjoyable: there was talk of events, sports and culture, of fashion and bullfighting – a thematic variety that was supported by photographs. Its journalists spent the day up and down, because Emilio Romero and his chief editor, Jesús de la Serna, encouraged street reporting. When she had been in Pueblo for a few months, where she would be, for about five years, the only photographer in the newsroom, and without having reached the age of thirty, on June 1, 1964 she saw her previous work in El Mundo Deportivo rewarded thanks to the trophy awarded by the Vice President of the Government: the Award for Merit in Graphic Information, one of the highest awards that sports photographers of the time could receive.

At that point in her life it was clear that Joana was living ahead of her time. Not only was she the first woman in Spain to work as a photojournalist, but she also did so without giving up her femininity or her freedom and decision-making capacity, quite the opposite of the image of a woman submissive to her husband that much of the Spanish society had assumed. For that reason she perhaps knew that it would not be easy to have a romantic relationship with a Spaniard.

One day, Alberto Oliveras, like her, a Catalan journalist based in Madrid, told her that a French boy had arrived who would work with him on SER’s “You are Formidable”, the first solidarity radio program in Spain, a true mass phenomenon. Oliveras asked her if she could show him a bit of Madrid. Joan accepted. That French journalist was called Jean Michel Bamberger and he turned out to be her better half. The chemistry between the two emerged from the first moment and they became inseparable. In addition, Jean Michel came from a country that was much more advanced in its uses and customs than Franco’s Spain, and he not only understood Joana’s approach to life, but also opposed the prevailing machismo in Spain.

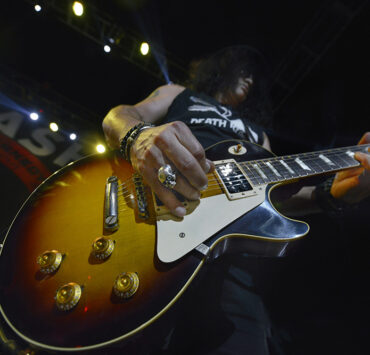

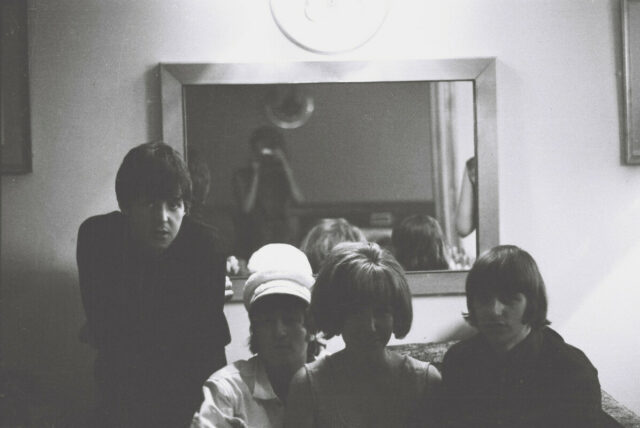

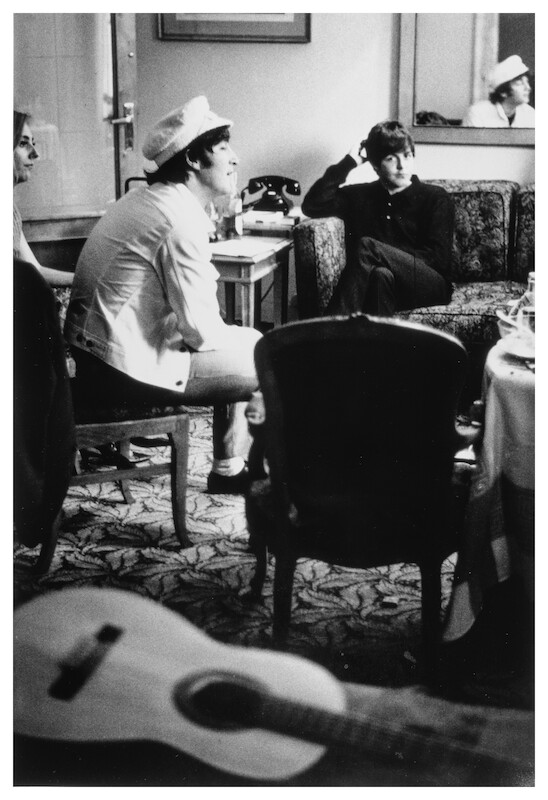

Three hours with the Beatles

Joana’s entry as a paid photographer in Pueblo coincided with the visit of the Beatles. On July 1, 1965, the Liverpool quartet arrived in Spain. That year had begun with university demonstrations for freedom of association, so the uncomfortable visit of those young people who were associated with drugs and a not very exemplary life did not make the authorities of the time, who had done, without success, everything possible to prevent that visit. Joana covered the group’s arrival at the airport, as well as the massive press conference at the Fénix hotel in Madrid. But those photos had nothing original and she was not happy.

The next day she was at the concert where she not only photographed the Beatles, but also personalities from the public, such as Ava Gardner or Rocío Durcal. Thanks to the good relationship she had with José Luis Ceballos, public relations for airline Iberia, she got a ticket for the flight that the group would take the next day to go to Barcelona, where a second and last concert was scheduled. That was how that July 3, once inside the plane, she went to the bathroom from where she photographed the members of the group, who were only a few meters away. In the end, she perked up until the security officials discovered her and asked her to leave. Those photos were something else. They were different, unique, though she decided that wasn’t enough.

When she arrived in Barcelona, the Beatles settled in the Avenida Palace. Joana knew the hotel staff and asked if there was a way to get to the room where they were staying. “Forget it,” they warned her, “there’s security at the elevator door.” “And on the forklift?”, she asked. They didn’t know. So she tried it and got lucky. No one was watching the forklift. She went into the bedroom and knocked on the door. Ringo Starr opened. —You? he asked, surprised. He remembered her from the plane. “One picture only,” Joana pleaded in broken English. He agreed. And that was how, suddenly, she was alone in the room with the Beatles.

Friendships and experiences

The anecdote with the Beatles gave Joana more fame among her colleagues, although the already famous knew her very well because she covered everything from social chronicle to the world of entertainment, fashion and culture, which allowed her to photograph the main characters of the sixties and seventies in Spain. Many of them had a great relationship with this smiling woman with an open character to whom they could trust their secrets. This is how she established friendship ties with Joan Manuel Serrat, Pilar Miró, Sara Montiel, Dalí, El Cordobés, the Duchess of Alba or Lola Flores, among many others. This not only allowed her to be close to them when necessary (Lola Flores, for example, only told her the day she organized a party at her house, where Yul Brinner and Audrey Hepburn were present), but also to get unique photographs that distilled proximity and offered a different look. She also knew how to offer an original look in fashion photography.

Behind that festive and famous atmosphere of Franco’s Spain, however, authentic dramas took place. As in the San Fernando center in Madrid, run by Salesians and which took in orphans and children of single mothers. There the children went hungry and violence and sexual abuse were the daily bread. Things began to change as a result of the visit, in March 1968, by Joana and José Luis Navas. The center was warned that two journalists would go, but even so those responsible failed to hide the mistreatment.

Raphael’s photographer

In those years the Raphael phenomenon had already emerged; the young singer who dazzled teenage girls. Emilio Romero told Joana to accompany him wherever he went. Raphael sold records but he also managed to sell many newspapers. Little by little, their relationship would become more intense until she became her personal photographer. She accompanied him on his tours and was in charge of the album covers. In 1972, Emilio Romero suspended Joana from employment and salary for a month after a colleague of hers, envious of her constant trips with Raphael, complained about how little Joana appeared in the newsroom.

At that time, the atmosphere in Pueblo had become rarefied, as well as the political situation, since the end of Francoism was already felt. Joana, dissatisfied with their decision, left the newspaper, ending a period of nine intense years. That was not a problem, because she had a lot of work with Raphael. In addition, Luis María Ansón, deputy director of ABC, had been insisting for some time that she go to work for the Luca de Tena newspaper and team up with journalist Natalia Figueroa, who would marry Raphael that year and with whom Joana had an excellent friendship. So it was. From then on, Joana’s life revolved around Raphael and Natalia.

At that time, Joana began to alternate that job with that of some agencies. She was director of Cosmopress and head of reporters at Contifoto until she, with Jean Michel and other colleagues, set up her own agency. First it was Sincro Press —where she had the support of professionals such as her secretary, María Jesús González, or the journalist Paola Ungareli—, and then Heliopress. A time, that of her own agency, in which she, above all, dedicated herself to covering film shoots in Hollywood. Thus, for example, she was on the set of Front Page by Billy Wilder. During a break in filming, she began to photograph Jack Lemmon, who took advantage of downtime to play the piano. “Is she coming from Spain to photograph me?” Well, I am important! Lemon joked.

Goodbye to journalism

With the arrival of the eighties and the establishment of democracy Joana was finally able to work without the dictatorship’s censorship. However, having greater levels of freedom and less social prejudice meant that there were more and more women photojournalists. Joana abandoned the profession that she loved so much. This is explained by the appearance of the paparazzi, unscrupulous photographers who would do anything for a photograph, especially of well-known personalities.

So, in 1985, with the same determination that she had applied to journalism for years, she now said goodbye to the profession, she put away the cameras and together with Jean Michel they began a new professional adventure in the hospitality industry.

Unexpected recognition

Joana was dealing with maculopathy when at her house showed up Cristóbal Castro, a photographer from Terrassa. He was preparing an exhibition of photographs from the 1950s on the floods and they had told him about her work in the midst of that drama. Joana looked for the images that she took at the time and Castro quickly realized their quality. It was then that she also discovered that file that had been locked up in boxes for more than twenty years and that was the chronicle of the most important events of the sixties, seventies and part of the eighties. It wasn’t just the floods. They were also Orson Welles, the Beatles, Raphael, the soldadera Herminia, the first hippies… Castro insisted on thoroughly studying the archive to organize an exhibition only with Joana’s photographs, who did not understand the value he saw in those photos.

When Castro was immersed in this work, he had a casual chat with the person who writes this text, which aroused the interest of the REC production company, made up of Òscar Moreno and Xavier Baig. From there arose the project of a documentary on the life and work of Joana. From then on, everything accelerated. The following years were hectic. First, in the summer of 2014, the Terrassa exhibition took place, the first anthology of her work (“The face, the moment and the place”) organized by the city council of this town in the central Sala Muncunill. In the spring of 2015, the documentary “Joana Biarnés, una entre todos” about her life was screened in cinemas throughout Spain, broadcast on television (TV3 and TVE). It also participated in various competitions, being recognized with several awards, such as those of the Malaga festival, the Reus Memorimage or the International of Documentaries of Barcelona, among others. In total, between cinema and television, the film accumulated half a million viewers.

Although Joana had already participated in the Albarracín Photography and Journalism Seminar as a special guest and the publishing house La Fábrica had dedicated an issue of the renowned Library of Spanish Photographers (PHotoBolsillo) to her, the documentary definitely boosted her figure. The professional sector and institutions turned to her and Joana began to collect awards and decorations. The Creu de Sant Jordi of the Generalitat de Catalunya, the Medal of Honor of the city of Terrassa, the gold badge of the Graphic Informants of La Rioja, the award for a career from the Federation of Publishers in the Catalan press or the Juan José Castillo of Journalism of El Mundo Deportivo are some of them. To these awards was added the production of two more exhibitions on her work, which in recent years can be visited in different cities of Spain.

Joana lives this recognition with the same enthusiasm that one day long ago turned her to journalism and that, moreover, comes to her with the camera hanging from her neck. Because, at the age of eighty and with only 30 percent vision, Joana decided to return to photography; and she did it without losing an iota of everything that has marked her career: humility, tenacity, coherence and fighting spirit.

Web sites: