+5

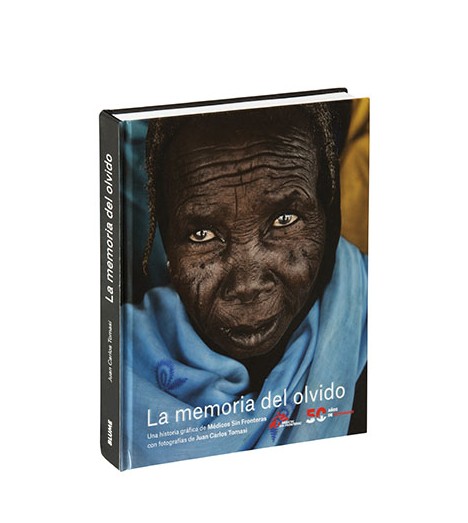

+5 Photographs: Juan Carlos Tomasi

Text: Ramón Lobo

The United States and its allies leave Afghanistan, after twenty years of war, without changing the lives of its inhabitants. Most are still trapped in a cycle of poverty, despair and violence, the same as before the arrival of the “saviors”. Missing was a deep knowledge of the history of an indomitable country and asking the people who are the protagonists before defining the context and establishing priorities.

The West decided that the burqa, a traditional garment that completely covers the body and face of Afghan women, was the center of the battle between tradition and modernity. On it we raised a narrative of the liberation of Afghanistan. The goal was to emancipate women, offer them a face, the right to visibility. Twenty years later, nothing has changed, except in parts of Kabul and Mazar-i-Sharif. The failure is resounding.

We never understood that the problem is not the clothing, but the reasons why women wear it and the difficulties they face in taking it off in a rural, macho and tribal society. To suppress the effects, we must work on the causes. If the score is not rewritten, the music never changes. Sustained progress moves in the little things. The real fight is inch by inch, while the propaganda promises miles that never come. I met an Afghan surgeon from Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) stationed in Nigeria. We were talking about his country, not about Africa. He was still angry because at a Congress in Paris, from which he had just returned, he had been asked about “the strange garment Afghan women wear.” He said that, for him, it was the jeans that were strange, because he had grown up in a family environment in which all the women wore the burqa outside the home.

The surgeon stayed at his post in the Kabul hospital when the Taliban seized power on September 27, 1996. After a while, a senior Taliban chief arrived with his sick wife. The surgeon informed her that he needed to check her, see parts of her body to determine the ailment and decide on the solution. The big boss angrily refused, and demanded a female doctor.

The surgeon told her they had a problem because Afghan women rarely went to college and now, with them in government, they didn’t even go to high school. “We cannot wait for a girl to overcome obstacles and finish medicine, because before that happens, your wife will be dead.” The Taliban chief then asked about the foreign doctors. The surgeon replied that, with what they paid, no doctor from Muslim countries had wanted to go to Afghanistan. “I am the only option for your wife to survive.”

After thinking about it for a long time the Taliban chief allowed him to see his wife’s body, and later to touch it during surgery. The woman was saved. She just had appendicitis, the surgeon told me with a wink. He was convinced that this experience had planted in that man a doubt more powerful than the bombs. Those doubts are what move the story inch by inch. In Kabul’s mountain with TV antennas, which separates the old city from the new, almost every child wanted to be a doctor in 2009. I asked why. They told me they were watching an Indian TV series about hospitals. Not only is it a profession that helps others, it is also a job that guarantees status. The candidate in that year’s presidential election, Ramazan Bashardost, told me, sitting in his tent opposite Parliament: “They have sent us everything we have in excess, weapons, bombs and soldiers; It would have been smarter to send TV series.”

Bunia was the ass of the world in June 2003. Major television networks and political attention were focused on Iraq, recently invaded by the United States. Saddam Hussein was still hiding in a dump dug out of a farm in Tikrit, his home village. No one looked at this corner of the Congo, north of the Kivus and close to Uganda and Sudan, where two tribes – the Hemas (cattle ranchers) and the Lendus (farmers) – repeated on a small scale the hatred and massacres that ended in 1996 with about 800,000 Tutsis and moderate Hutus in Rwanda.

France, distanced from the action that was taking place in the Middle East, decided to send troops under the umbrella of the European Union. The declared objective was to support a small detachment of UN Blue Helmets, most of them Uruguayans, with hardly any means to impose peace or to defend themselves against attacks. The sudden Westernization of a distant conflict helped my bosses at El País, the newspaper I worked for at the time, understand the urgency of covering the news.

It was not my first mission with Juan Carlos Tomasi, nor would it be the last; some within the MSF structure, such as the one in Somalia in 2007, and others outside, relying on his experience and presence on the ground to carry out the work.

We arrived in Uganda, the logistics gateway to Bunia, in the rush of those who feel that they are late for an appointment. The French military and the UN transport planes did not bring in journalists. My only option was to convince the MSF official in Kampala. After a time that seemed like forever and a couple of calls, he accepted me on board to fly the next day. He only set two conditions, which included Tomasi: “As soon as we arrive, you get off the plane and I don’t know you; how to get to the city will be your business and if things get screwed up, I won’t get you out.” We accepted out of unconsciousness and the hope that he would not leave us stranded after evacuating all MSF staff.

At the Kampala airport we were greeted by a pilot who looked like something out of a UVA session, with a tight shirt and thick hair. It didn’t make the best impression on me. Before taking off he explained that the landing would be in a dive for safety reasons and that we should let him know immediately if we felt sick, to smooth it out a bit. Tomasi started bragging about a crash landing in Angola, which I thought was a terrible idea. This was not the time to provoke a guy who had our lives in his hands. After flying over some beautiful lakes that served as the border between Uganda and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, we saw several destroyed villages and a distant runway.

The pilot lunged at it with such violence that I was unable to make a complaint. I had my whole body upside down, my tongue out of control, my eyes bulging out of their sockets and a huge headache. At that time I would have killed Tomasi. After landing with the smoothness of a Boeing 747, we picked up our bags and began the task of looking for life. It was luck that a UN plane with a chief on board had just arrived, which served as a knock-on effect for a few journalists. We got out in the back of an Associated Press pick-up. We slept the first night in the open in the Blue Helmets barracks. In the following ones, we achieve some spartan rooms in a mission of the White Fathers. We worked hard for days to report the situation.

MSF had a field hospital halfway between the city and the airport, next to other humanitarian organisations and a large camp for displaced people. A shaven-headed Neapolitan surgeon named Vincenzo Poleze operated on it for hours. Seeing him sitting outside one day, exhausted on a rusty bench, bathed in sweat and smoking, I said to Tomasi: “Juan Carlos, that guy has a story.” He seemed to me the personification of the invisible hero, a person who accumulated all his vacations and days off to carry out his work in a forgotten place. He was someone who represented thousands of other workers and volunteers without the right to a photo and caption that make us better as a society.

When I hear the complaints about booze and movement restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic, or the laziness to wear a mask, I think of the essential people who give themselves, fight and help, and of the millions to whom the lottery of life distributed bad luck without the right to food, physical security and justice. And in those who drown in the Mediterranean and the Atlantic, those who never reach the American dream or die in distant wars under our bombs made in the West.

It is fortunate and a privilege to have a job like Juan Carlos Tomasi’s at MSF. It allows you to document pain and hope, to put faces and names to the invisible, to reveal their stories to us so that no one in our world of three hot meals a day, clean water and pay TV series can say “I didn’t know”. It is a blessing and a privilege to meet hundreds of Vincenzos, men and women, locals and expatriates, who dignify humanity. Thanks for that, comrades.

About the Author:

Juan Carlos Tomasi, 1959, Journalist and photographer. From Barcelona, born in Madrid. His camera has captured images in a wide range of scenarios and historical moments around the world. From the displaced people of Congo and Rwanda to the victims of the Balkan war, from the numerous natural disasters to the humanitarian coverage of major epidemics, he has tried to find, from the other side of the daily news, stories of lives that dignify and give prominence to the victims. He began as a sports journalist, and worked on the 1992 Barcelona Olympic Games. But his career took a radical turn to focus on conflict coverage and humanitarian journalism. He has been a producer and director for several international media. Since 1995 he has been a photographer and reporter for the international humanitarian organization Médecins Sans Frontières. His gaze has contributed to share with the public almost all the forgotten conflicts of the world during the last twenty-five years, working for media such as El País, La Vanguardia, El Periódico, The Independient… He also collaborates with other international aid organizations to disseminate the consequences of humanitarian disasters and climate change. He has published several books and has exhibited his work in many cities around the world.

Links:  Libro en Blume.net

Libro en Blume.net